Wisconsin | Wisconsin Gazette - Smart, independent and revealing. News, opinion and entertainment coverage

A 42-inch pipeline buried beneath every major waterway in Wisconsin would dwarf the volume of gritty, chemical-laced sludge carried by Keystone XL when it amps up operation next year. Only a Dane County zoning committee stands in the way — temporarily — of oil giant Enbridge’s intention for Line 61 to convey more tar sands crude than any pipeline in the nation.

A network of pipes and pumping stations built at various times and gradually joined together, the convoluted line began in 2006 and currently pumps an astonishing 560,000 barrels through Wisconsin daily. After its 12 pumping stations are either constructed or upgraded with additional horsepower, the line would convey up to 1.2 million barrels daily — one-third more than the Keystone XL’s 800,000 barrels.

Enbridge, North America’s largest oil and gas pipeline operator, has the Western Hemisphere’s worst record for spills. The National Transportation Safety Board has recorded 800 incidents since 1999 — and that’s not including oil that seeps into the environment from weak or corroded sections of pipe, which is ignored by federal regulators.

According to the Wisconsin League of Conservation Voters, Enbridge is guilty of more than 100 environmental violations in 14 Wisconsin counties. Most recently, in July 2012, a farm field in Grand Marsh was covered by at least 1,200 barrels of oil after an Enbridge pipeline ruptured. Enbridge had to purchase a nearby home that a local resident described as being “covered in oil,” according to the Sierra Club. The rupture involved conventional crude oil rather than tar sands crude.

“Enbridge is a high-risk company,” said Elizabeth Ward, conservation program coordinator for the group’s John Muir chapter in Wisconsin.

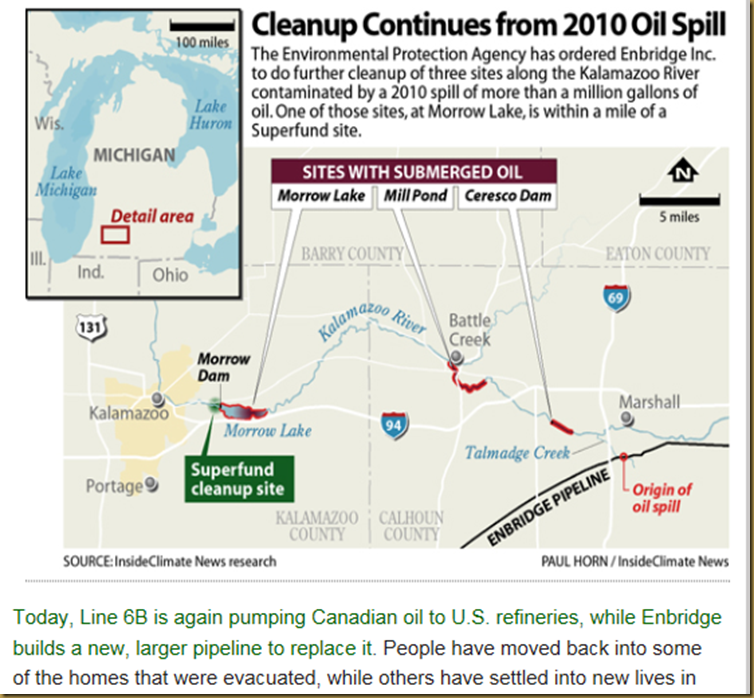

Enbridge also is notoriously dodgy about accepting responsibility for its mishaps. In 2010, the break of an Enbridge line in Michigan spewed tar sands oil for more than 17 hours before Enbridge realized it was leaking. Some 20,000 barrels of tar sands crude damaged 35 miles of Michigan’s Kalamazoo River. The full extent of public health effects will probably never be known, but 320 homes were evacuated.

It was the largest inland oil spill in the nation’s history.

The EPA ordered Enbridge to clean up the impacted area by the end of 2013. After some pushback, the company agreed to comply.

But Enbridge has spent more than $1.2 billion on the cleanup and it still has yet to be completed. Some question whether it ever can be.

The company claims to have refined its operations since then, significantly increasing safety.

In the shadows

Why has Keystone generated such frenzy while Line 61 has gone largely ignored? For one thing, Keystone is a new pipeline without a track record. Another is partisan politics. Republicans pushing for the president’s approval of the Keystone XL have used his stated environmental concerns to charge that he’s “anti-jobs.” The actual number of jobs created by Keystone and similar projects, however, is surprisingly modest, given the rhetoric.

Like the tar sands sludge that would be carried by Keystone, the crude transported by Line 61 also originates in Alberta, Canada. It arrives in Superior, Wisconsin, by way of a line known as the Alberta Clipper. But Line 61 itself is confined within American borders, so no presidential approval is required.

A more significant reason for the lack of public interest in Line 61 is that Enbridge seems to have learned a public-relations lesson from the drama over Keystone, Ward said. In order to avoid a reprise of Keystone, Enbridge has kept Line 61 as low profile as possible. The company also resorted to what Ward and other critics believe is subterfuge by breaking the entire project into three pieces, each of them addressed without fanfare.

Thus, the company was able to build the complex pipeline (see diagram) in the shadows, sidestepping public meetings for the most part. Environmental advocates say the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources assisted the company by virtually rubber-stamping the project every step of the way.

By the time advocates put the pieces together and realized the full scope of Enbridge’s plan, all of the pipes were in place, and most of the 12 pumping stations were either ready to operate or already approved. Eleven of the 12 now have use permits.

Once environmental groups realized what was going on, they found themselves helpless to stop the juggernaut.

Becky Haase, a stakeholder-relations specialist for Enbridge, has said everything the company did was up front and on the level. According to her, the pipeline was constructed specifically to move large amounts of oil sands through the region.She said the pipes already laid were built to run up to 1.2 million barrels per day and additional permits are not needed.

Environmentalists, however, are horrified that the nation’s largest tar sands pipeline, created and operated by the nation’s most accident-prone distributor, was erected without conducting an environmental impact study. Six Wisconsin counties recently passed resolutions asking the DNR to do a large-impact study on the tar sands project in its entirety, Ward said. The agency, however, contends that it’s not needed.

The DNR has not been helpful to any of the counties concerned, multiple sources told WiG. And, they added, it’s highly unlikely that the agency will change course, given the state’s current political environment. Fossil fuel companies such as Koch Industries might not employ that many Wisconsinites, but dozens — if not hundreds — of public officials have accepted what adds up to massive amounts of cash from them.

Yet one of the toughest problems facing environmental advocates in Wisconsin is the blind trust residents put in their leaders to shield them from harm. “(The public) automatically assumes that there’s no way we can be right and Gov. Walker and the DNR could be misleading them,” Ward said.

And, since gag orders inevitably come with the settlements that residents receive from oil distributors, there’s no one around except for activists to tell the public the truth.

Hands tied

The only remaining holdout on Enbridge’s Line 61 is the Dane County Zoning Committee. For months, the committee has delayed approval for the project’s 12th pumping station, which Enbridge plans to build in the county’s northeastern corner — an area of farmland and wetland. The latest delay was Jan. 28.

Chair Patrick Miles said that while constituents have brought concerns about the project to his attention, the committee lacks authority to address their fears of prospective disasters. Some people, he said, brought their concerns to him privately, afraid to speak up publicly because they receive lucrative easements from Enbridge to allow pipelines on their properties. They fear retaliation, Miles told WiG.

“This particular permitting process has been more frustrating than most, because our hands are tied,” he said. “Usually we have the authority to at least consider a denial if we can’t mitigate concerns, but there’s not an option here. It’s a foregone conclusion that they’ll get their permit — the question is under what terms.”

Eventually, the zoning committee hit on the strategy of requiring Enbridge to show proof of adequate insurance to handle damages should something go awry. Residents should at least have assurances that their financial losses would be covered in the event of a disaster, Miles said.

For the last few weeks, the committee has frenziedly researched what kind of costs would be associated with various disaster scenarios and what kind of insurance — and insurers — would handle them.

Miles said Enbridge officials began their interaction with the committee by being uncooperative, saying the county had no legal right to request insurance coverage. Miles said he was intimidated by the prospect that the oil giant would slap the county with an expensive lawsuit.

But the county’s concerns are well-founded, say others. Enbridge is a limited liability corporation that says it’s self-insured, but the company has very little value. The partners distribute profits among themselves as the money pours in and have little left in the way of assets after the oil is sold.

The $1.2 billion that Enbridge has paid so far to restore damage on the Kalamazoo River has been paid on a “pay-as-you-go” basis, with money coming out of the company’s revenue stream, says Harry Bennett, of the group 350 Madison.

With the specter of Kalamazoo overshadowing them, Miles and his crew refused to back down. The county’s legal counsel dug into the relevant case law and discovered that proof of insurance is a perfectly legitimate request. After the county’s standing was established, Enbridge’s attitude seemed to improve.

“They’re being pretty patient now,” Miles said.

Enbridge had recently taken out a $700-million insurance policy and representatives of the company offered to designate $100 million of it specifically for any mishaps that might occur in Dane County. Enbridge officials also pointed out that the Pipeline and Hazardous Chemicals Safety Administration operates an oil spill trust fund that would make up any differences in costs.

At the committee’s Feb. 10 meeting, as WiG was headed to press, members planned to press Enbridge on conducting an environmental risk analysis, something the company has indicated it’s open to doing, according to Miles. The analysis would pave the way for obtaining adequate insurance.

Miles speculates that the precipitous drop in oil prices coupled with Obama’s hesitancy toward the Keystone pipeline might have taken some urgency out of the push for Line 61. The Alberta Clipper, which feeds tar sands into Line 61 and other U.S. pipelines, also needs presidential approval, according to the Sierra Club, which has joined other groups in filing a lawsuit forcing the company to get presidential approval. and so it’s possible that Enbridge does not want to draw too much attention to the project right now.

Gummy peanut butter

Environmentalists say it defies logic that regulators treat conventional crude and tar sands crude as if they pose the same safety risks, because they are vastly dissimilar materials.

Technically known as “bituminous sands,” tar sands crude is a mixture of petroleum, clay, sand, water and chemicals that allow the thick, abrasive sludge to flow through pipelines. Bennett calls it “gummy, peanut-butter-like stuff.”

Tar sands are heavier and far more abrasive than conventional crude, and the chemicals used to dilute it are very acidic. That means the erosion of pipe walls occurs much faster and the threat of rupture is far keener on pipelines conveying tar sands crude.

Similarly, tar sands accidents do far more damage to the environment and are exponentially more difficult and expensive to clean up. Unlike traditional oil, tar sand oil is dense and does not float. As the accident in Michigan proved, lumps of chemically treated tar sand remain on the floor of riverbeds and ponds long after surface evidence has disappeared — perhaps forever. The acidic damage to the affected waterways remains unknown.

Technology to detect leaks before they mushroom into irreparable disasters is all but useless. The detection system is supposed to have automatic shut-off valves that are tripped when a leak is found. But a Natural Resources Defense Council investigation discovered that the systems missed 19 out of 20 of the smaller spills — and even four out of five of the larger spills.

“If we were in a different political state and nation, there would be a completely different process for tar sands pipelines,” Ward said. “We’re (operating under) antiquated rules that do not differentiate between the types of oils.”

“Tar sands are the least efficient and most difficult oil to extract,” Bennett said. “There should have been an environmental impact study done in 2006 or 2007, when all this was ramping up.”

Many people also wrongly assume that the tar sands pipelines carry oil that is consumed domestically and helps to keep down their fuel prices. But the contents of Wisconsin pipelines, just like the contents of the proposed Keystone XL, are destined for overseas markets. Right now, Enbridge’s tar sands crude is headed nowhere, because the cost of mining and processing it is either close to or greater than the cost of the average barrel of oil sold in the marketplace.

In the end, tar sands passing through pipelines in Wisconsin are bound for refineries and then storage tanks, where the oil will sit until prices rebound. Wisconsin is just a pass-through state that will see little if any economic benefit by way of gas or jobs.

“While the overseas markets will see the benefits, Wisconsinites are expected to take all the risks,” Ward said.