On the last Saturday of August 2013, Labor Day weekend, the United States was once again about to go to war in the Middle East.

Less than two weeks earlier, in the middle of the night on August 21, the Syrian military had attacked rebel-controlled areas of the Damascus suburbs with chemical weapons, killing nearly 1,500 civilians, including more than 400 children. Horrific video footage showing people with twisted bodies sprawled on hospital floors, some twitching and foaming at the mouth after being exposed to sarin gas, had ricocheted around the world. This brazen assault had clearly crossed the “red line” that President Barack Obama had enunciated a year earlier—that if Assad used chemical weapons, it would warrant U.S. military action.

Heading into the long weekend, the Pentagon had made plans for round-the-clock staffing, since we thought the military operation would start over the holiday. As the assistant secretary of defense for international security affairs, I had been involved in the deliberations and planning for the strikes. Yet early Saturday morning, I received a call from Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel’s office with surprising news: The president had called Hagel late the night before and told him he “wanted to explore another option.” Instead of ordering strikes immediately, the president wanted to pump the brakes and first go to Congress to ask for its authorization.

So when the president stepped into the sunny Rose Garden that Saturday morning, he announced that he had made two decisions: first, that the U.S. should act against Syria, and second, that he would seek explicit authorization from Congress to do so. With that, the administration set out on a different campaign than the military one we had been preparing for: to convince the American people that intervening in Syria was in the country’s interest.

What transpired over the next month was one of the most controversial and revealing episodes in eight years of Obama’s foreign policy. Despite the administration’s strong advocacy and support from a small minority of hawkish politicians, Congress and the American people proved strongly opposed to the use of force. In the end, however, the threat of military action and a surprise offer by Russia ended up achieving something no one had imagined possible: the peaceful removal of 1,300 tons of Syria’s chemical weapons (there have been reports of stray weapons and widespread use of industrial chemicals like chlorine, but no evidence of systematic deception on the part of the Syrian government).

By October 2013, without a bomb being dropped, the Bashar Assad regime had admitted having a massive chemical weapons program it had never before acknowledged, agreed to give it up and submitted to a multinational coalition that removed and destroyed the deadly trove. From my perspective at the Pentagon, this seemed like an incontrovertible, if inelegant, example of what academics call “coercive diplomacy,” using the threat of force to achieve an outcome military power itself could not even accomplish.

Yet the near unanimous verdict among observers is that this episode was a failure. Even the president’s sympathizers call the handling of the red line statement and its crossing a “debacle,” an “amateurish improvisation” or the administration’s “worst blunder.” They contend that Obama whiffed at a chance to show resolve, that for the sake of maintaining credibility, the U.S. would have been better off had the administration not pursued the diplomatic opening and used force instead. In this sense, a mythology has evolved around the red line episode—that if only the U.S. had used force, then it could have not only have addressed the chemical weapons threat, but solved the Syria conflict altogether.

ADVERTISING

But this conventional wisdom is wrong. Of course, some of the criticism can be explained by politics, with partisans unwilling to give Obama credit for any success. But many others criticize the policy less for its outcome than for the way it came about. This line of judgement reveals a deep—and misguided—conviction in Washington foreign policy circles that a policy must be perfectly articulated in order to be successful—that, in a sense, the means matter more than the ends. Far from a failure, the “red line” episode accomplished everything it set out to do—in fact, it surpassed our expectations. But the fact that it appeared to occur haphazardly and in a scattered way was enough to brand it as a failure in Washington’s eyes.

***

According to U.S. estimates, at more than 1,300 metric tons spread out over as many as 45 sites in a country about twice the size of Virginia, Syria’s arsenal of chemical weapons in 2013 was the world’s third-largest. It was 10 times greater than the CIA’s (erroneous) 2002 estimate of Iraq’s chemical weapons stash, and 50 times larger than the arsenal Libya declared it had in late 2011. Because of the size and scope of the threat, Syria’s chemical weapons were the administration’s top concern during the first several years of the crisis. I spent the better part of two years worrying over what to do about them.

So when I first heard about Obama’s decision to take the question of using military force in Syria to Capitol Hill, I was shocked. I had been in most of the White House meetings about Syria up to that point, and while the issue of legal authorities and Congress had come up, it was clear the president had all the domestic legal authority and international justification he needed to act. The idea of asking for a congressional vote had never been discussed at length; some had suggested we should ask for a vote, but there was skepticism it would pass, and therefore a feeling the question should not be asked. For an administration that prized careful and inclusive deliberation, it was unusual that a decision this big would arise so suddenly without first being thoroughly pored over in the interagency process.

But once the surprise wore off, I found myself thinking that, while abrupt, unexpected and unorthodox, this was the right move. Not for any legal reason or question of constitutional powers, but because after a decade of war in the Middle East, Congress and the American people needed to be fully invested in what we were about to do and prepared to accept the consequences.

The civil war in Syria had dominated the news for more than two years, but few politicians had thought deeply about it, relieved that it was not their problem. None were happy to share the responsibility of being accountable for what America would or would not do about the violence. And, in fact, now that they did share the responsiblility, it became clear that they were as uncertain as the administration had been about the risks of using force—and fears of the possible consequences.

For two weeks, the administration made its case on Capitol Hill, but it soon became clear that most Republicans and Democrats in Congress were against authorizing action—leaving Obama the option of going forward anyway (which he said he would do) or backing down altogether. Then, an unexpected opportunity emerged: During a September 9 news conference in London, Secretary of State John Kerry was asked whether there was anything Assad could do to avoid an attack. Sure, Kerry said in exasperation, the Syrian leader could admit that he had chemical weapons (something he still refused to do) and give them all up peacefully, but “he isn’t about to do it and it can’t be done.” Like Obama’s original red line a year earlier, this offhand remark wasn’t intended to be a policy pronouncement. But soon after Kerry walked off the stage he received a call from his Russian counterpart, Sergei Lavrov, who was then meeting with a delegation of Syrian diplomats in Moscow and wanted to talk with the secretary of state about his “initiative.”

Washington and Moscow had deep disagreements over Syria. Russia continued to be one of Assad’s few international backers and, importantly, the Syrian military’s chief supplier. But even Moscow worried about Syria’s chemical weapons. And though earlier talks of U.S.-Russian collaboration to deal with Assad’s stockpile had never led anywhere, the credible threat of U.S. military force suddenly changed the calculation. Now, Moscow was ready to pressure Assad to comply with Kerry’s offhand demand. Maybe this reflected Russian concerns about the proliferation of chemical weapons; or perhaps this was driven by the Kremlin’s desire to keep an ally in power; or possibly Russian leaders were simply trying to stay relevant geopolitically. Whatever the reason, the next day, following a meeting with the Russians in Moscow, the Syrians publicly admitted for the first time that they had chemical arms and committed to signing the Chemical Weapons Convention, the international treaty banning such weapons. The Syrians were pledging to come clean—and not just to reveal what they had, but to get rid of their chemical weapons altogether.

Initially, the Obama administration approached the Russian offer, and Syria’s compliance, skeptically. Putin and Assad had every reason to want to delay U.S. military action. Moreover, the idea of dismantling Syria’s stockpile was daunting—there seemed to be thousands of steps before we could be sure something like this had any hope of working. But Obama wanted to test the proposition. After all, if not using force enabled the U.S. to achieve something that was unquestionably in its security interests and had once seemed impossible, how could he not consider taking such a deal?

With U.S. Navy ships still ready to launch strikes, American and Russian diplomats spent several days hammering out the specific steps Syria would take to allow international inspectors to find, remove and destroy its chemical arms. The Syrians signed on, and the U.N. Security Council endorsed the deal, while also authorizing international action if Assad failed to comply. In just a matter of weeks, the administration had gone from plotting over how to deal with one of the world’s largest arsenals of chemical weapons to implementing a plan to eliminate all of them.

***

Despite the unexpected success of the whole episode, Obama’s sudden pivots—first abruptly pausing to go to Congress, then seizing a surprise opening for diplomacy—struck many in Washington and abroad as unseemly. It did not help that unscripted comments both got the U.S. into the situation (Obama’s original red line statement in August 2012) as well as out of it (Kerry’s public musing that Syria could avoid strikes by giving up its chemical weapons). Where the president saw nimble improvisations adjusting to new opportunities, the critics saw lurching indecision.

Many foreign leaders also asserted that failing to respond militarily had damaged the administration’s credibility. Although no Arab countries were willing to contribute their own forces and most Arab leaders refused even to support Obama publicly when he asked for their support, nearly all blamed him for not intervening. Even though the chemical weapons threat was removed, they questioned whether they could trust the U.S. to follow through on its commitments to them. Even some Europeans were disappointed—especially the French, who felt politically exposed as the only country that had declared itself willing to strike with the US. in September 2013.

Given such perceptions, it is worth reflecting on what might have happened had the U.S. barreled forward and attacked Syria as planned. Would we have been better off? In that case, it is highly unlikely that the tons of chemical weapons would have been safely removed from the country. Even if an initial salvo had deterred Assad from using more chemical weapons, he would still have had hundreds of tons at his disposal, since the strikes would have eliminated only a small fraction of his arsenal.

It is also safe to assume that there would have been absolute hysteria, with good reason, about such weapons being at large in a war-torn country—at risk of falling into the hands of ISIL and other terrorist groups. In fact, I believe that had Obama acted as he was ready to do in the fall of 2013, he would have ended up deploying substantial numbers of American troops to Syria to secure those remaining chemical weapons depots over which Assad likely would have lost control. And if Obama had done that, and had the chaos of the attack led in turn to a loose chemical weapon being used to strike Israel or conduct a terrorist attack in the U.S. or Europe, he deservedly would have been blamed and held accountable.

Perversely, critics at home and abroad treat the removal of Syria’s chemical arsenal as an afterthought—as minor and insufficient—and instead choose to assert that Obama soiled America’s reputation. It is as though they place higher value on being “tough,” especially if it involves military force, than on lasting accomplishment. In the name of maintaining “credibility,” they criticize Obama for not acting militarily, even if doing so would have delivered a less advantageous outcome for our overall security.

This is especially odd given our recent past. The U.S. went to war in Iraq in 2003 to address a WMD threat that did not exist, and the devastating result cost resources, took thousands of American lives and wounded many others, tarnished U.S. leadership, and unleashed a regional firestorm we are still dealing with today. In Syria in 2013, the U.S. addressed a WMD threat that did exist—and was of far greater scale—by avoiding the use of force. Yet this is widely perceived as a blow to American authority.

How can this be? The first part of the problem is Washington’s obsession with “credibility.” Perceptions do matter, but I think Obama would agree with the point made by the political scientist Richard Betts, who observes that “credibility is the modern antiseptic buzzword now often used to cloak the ancient enthusiasm for honor. But honor’s importance is always more real and demanding to national elites and people on home fronts than it is to [those] put into the point of the spear to die for it.” Obama is openly skeptical of the Washington establishment’s preoccupation with credibility, believing that the logic sets a trap leading to bad decisions.

A second issue is process. Procedure and presentation matter too, and Obama concedes that the red line affair was not a textbook execution of foreign policy. “We won’t get style points for the way we made this decision,” he has said. By exposing the public to the sausage-making of policy—and by thinking out loud, making clear all the uncertainties and risks, and shifting directions abruptly—the administration created an impression that it lacked confidence. The whole episode also wasn’t predictable, and people don’t like that. Presidents get rewarded for linear results, especially when things happen the way the collective wisdom says they are supposed to.

Obama’s sudden, and clumsy, move to go to Congress for approval didn’t help matters. It was the right decision, but it should not have been made on the fly and with no consultation with our allies, especially the French, who were the only ones willing to act with us. To this day, many believe that going to Congress was just a cynical move by the president to pass the buck and avoid strikes. I never believed this to be true, and remain unaware of any evidence to prove such an assertion. Although Obama asked for congressional support—and, given the risks of action against Syria’s chemical weapons, believed it important to have a show of unity—he always made clear he would act without it.

A third problem is dashed expectations. By drawing the red line, Obama unintentionally fueled the hope of some that he would respond with overwhelming force. Or, as many now assert, he should have used the crossing as a justification to achieve a different goal, something that the red line was never about and military strikes were never intended to do: take out Assad.

To be sure, it has been hard for the administration to claim the red line as a strategic success because of the improvised way it unfolded. And it’s possible Obama could have achieved the same result through different means—means that might have generated a greater sense of American leadership. But that shouldn’t cloud how we remember the chapter: In foreign policy, the end result matters more than the road one took to get there.

Obama is fine with winning ugly: “I’m less concerned about style points,” he told an interviewer after he pulled back from using force in September 2013. “I’m much more concerned about getting the policy right.” When asked about the criticisms, Obama said that “folks here in Washington like to grade on style … and so had we rolled out something that was very smooth and disciplined and linear, they would have graded it well, even if it was a disastrous policy. We know that, because that’s exactly how they graded the Iraq War.”

What’s instructive—and for many of Obama’s critics, inconvenient—is to listen to the foreign leaders who are most complimentary of the way things turned out: the Israelis. Syria’s vast chemical weapons arsenal was an acute threat to Israel—a threat for which it had no viable military answer. Israeli military officials later told me that they had done their own planning for airstrikes to take out the chemical weapons, yet all the scenarios had “horrific” civilian casualties.

While some Israelis were initially very worried that by pulling back from military action Obama had undermined his credibility, they were relieved by the outcome. The removal of Syria’s chemical weapons is an accomplishment that Prime Minister Netanyahu, a leader who has had his share of disagreements with Obama, described as “the one ray of light in a very dark region.” Such sentiments were echoed repeatedly by senior Israeli defense officials, who by 2015 considered the Syrian chemical weapons threat so insignificant they did not include gas attacks as a scenario in their annual emergency home-front drills.

In the United States and many other corners of the world, the whole episode is remembered quite differently: It has morphed into a short-hand critique of Obama’s handling not just of Syria, but of his exercise of American power. Even inside the administration, the phrase itself has become loaded, as though it were a slur, politically incorrect to utter.

In fact, the red line chapter is emblematic of Obama’s foreign policy strategy: This kind of long-range, flexible, restrained and targeted policy is a hallmark of his unique approach to global problems. But instead of being seen as a mistake, it should be considered an accomplishment. Judged by what the red line was originally intended to do—address the massive threat from Syria’s chemical weapons—it was a success. In fact, it has been perhaps the only positive development related to the Syria crisis.

There is no question the Syrian war is the greatest catastrophe of the post-Cold War world, with hundreds of thousands of casualites, millions of refugees, states disintegrating and extremists filling the vacuum. But there is a question about what America can and should do about it. Numerous critics (including some former administration officials) have made the case that the U.S. should be willing to use additional military power to achieve its other stated policy goals—to accelerate Assad’s departure, build a lasting political settlement, combat extremists, or simply to reclaim authority. The challenge Obama faces is how to reconcile this understandable impulse to act with the desire to prevent a problem like Syria from overwhelming American foreign policy.

The debate is often defined as “doing something” or “doing nothing,” but those are false choices. The policy debate exists between these extremes—deciding the way to address a problem like Syria somewhere between being all-in (like the Iraq invasion in 2003) or standing aside entirely. How the United States has navigated these competing interests and managed the trade-offs is one of the central stories of the Obama presidency. And it is a defining characteristic of his long-game strategy.

Derek Chollet is Counselor at The German Marshall Fund of the United States, and served in the Obama Administration in the White House, State Department, and Pentagon. This article is adapted from the book The Long Game: How Obama Defied Washington and Redefined America’s Role in the World.

Above is from: https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2016/07/obama-syria-foreign-policy-red-line-revisited-214059

Rick Newman Fri, Apr 13 9:53 AM CDT

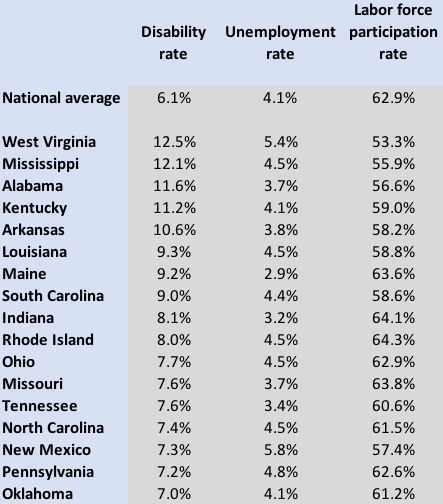

Rick Newman Fri, Apr 13 9:53 AM CDT Source: The Conference Board, Bureau of Labor Statistics

Source: The Conference Board, Bureau of Labor Statistics