Melissa Rossi 5 hours ago

A Mosso D’Esq uadra (Catalan regional police officer) salutes Spanish anti-corruption prosecutor José Grinda, center, as he leaves the Generalitat de Catalunya (Catalan government) in Barcelona in 2017. (Photo: Pau Barrena/AFP/Getty Images)

uadra (Catalan regional police officer) salutes Spanish anti-corruption prosecutor José Grinda, center, as he leaves the Generalitat de Catalunya (Catalan government) in Barcelona in 2017. (Photo: Pau Barrena/AFP/Getty Images)

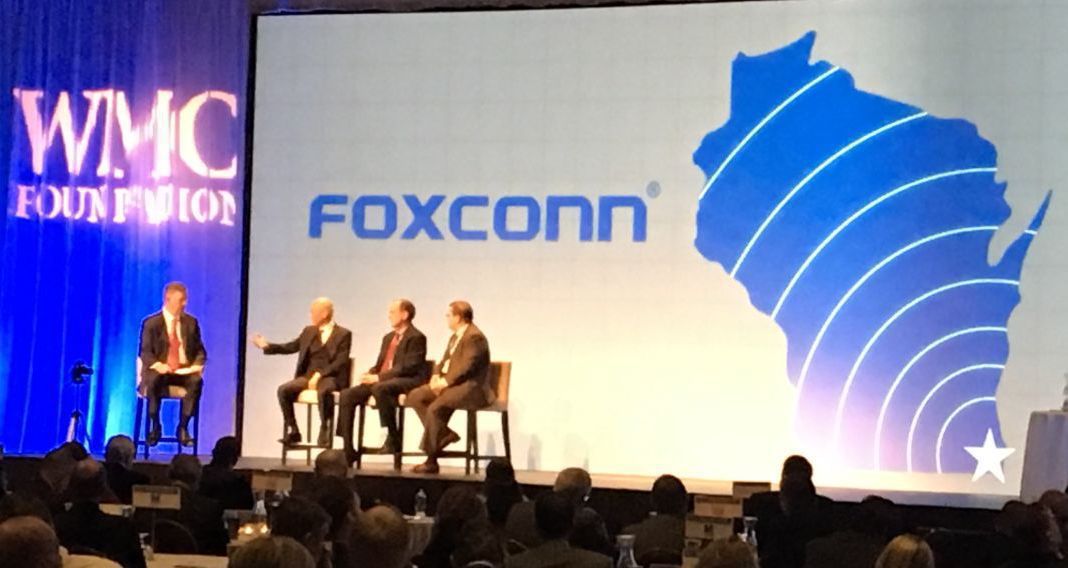

MADRID — Dawn’s first rays were streaming through the palm trees in Spain’s laid-back jet-setter paradise Marbella when the crashing of waves was drowned out by the whomp-whomp of hovering police helicopters and the wail of sirens. Roadblocks went up and streets were shut down all morning as more than 100 officers of the Guardia Civil, the Spanish military police, raced across the port city — storming villas, ritzy eateries, yachts, a golf course, the soccer stadium, a bank, even raiding a water-bottling plant deep in the dusty hills.

By lunchtime on that Tuesday, Sept. 26, 2017, the police had confiscated 23 luxury autos and hundreds of thousands of euros. They also arrested 11 Russians, including the beloved owner of the local soccer team, Alexander Grinberg, charging him with, among other things, membership in a criminal group — specifically Russia’s most powerful mafia, Solntsevskaya Brotherhood, the world’s richest, said to pull in some $9 billion a year.

A Spanish police report obtained by Yahoo News Chief Investigative Correspondent Michael Isikoff said the group was involved in “criminal activities including drugs, counterfeiting, extortion, car theft, human trafficking, fraud, fake ids, contract killing, and trafficking in jewels, art, and antiques. This was done on an international scale. Not just in Russia. Solntsevskaya has also demonstrated active cooperation with other international criminal organizations, like Mexican mafias, Colombian drug cartels, Italian criminal organizations (particularly with the Calabrian ’Ndrangheta and the Neapolitan Camorra), the Japanese yakuza, and Chinese triads, among others.”

Alexander Grinberg (Photo: Debbie Wallace)

Alexander Grinberg (Photo: Debbie Wallace)

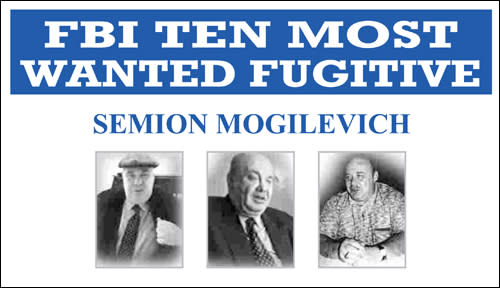

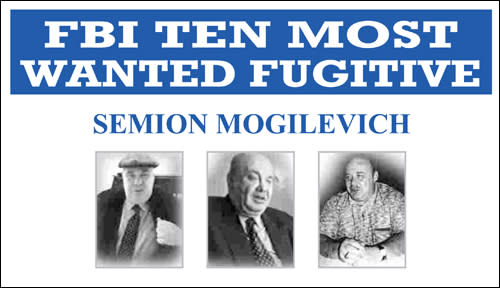

But the “big fish” of that day’s catch was former Russian hotelier Arnold Tamm, aka Spivakovsky, alleged to be a trusted aide to the notorious Semion Mogilevich — a Ukraine-born economist known as “the Brainy Don” whose photo long resided on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted list. He was described as a “Global Con Artist and Ruthless Criminal,” accused of bilking U.S. investors out of $150 million in a stock fraud. But above all, Mogilevich is a mastermind of cleaning up dirty money — using financial transactions that make the cash generated from criminal enterprises appear legitimate, and park it in accessible and safe investments in Western countries such as Spain or the United States, valued precisely for their adherence to legal norms.

Which is to say that morning’s drama in Marbella was all about money laundering, in this case more than 30 million euros (around $35 million) of illegal profits cleaned up in businesses from the Marbella fútbol club to the Lady of the Night golf course to the Agua Sierra de Mijas water-bottling plant.

And that’s why José Grinda, Spain’s own Robert Mueller, was in town.

Slim, bearded and exuding a calm confidence that belies threats against his life and Russian-sponsored smears of his name, Grinda — leading special prosecutor in the anti-corruption and anti-mafia branch of la Fiscalía, Spain’s attorney general’s office — also investigates corruption within his government, and conducts stings against crime groups of all sorts, Italian to Chinese. But his highest-profile raids — which have garnered Spain a reputation as the most fearless pursuer of mafia operations in Europe, and arguably the world — are directed at Russian organized-crime syndicates, which favor the Spanish economy to recycle the hefty proceeds from drug smuggling, gun running, prostitution and human trafficking. Cleaning up cash, Grinda says, is why the Russians began moving in to these shores more than two decades ago.

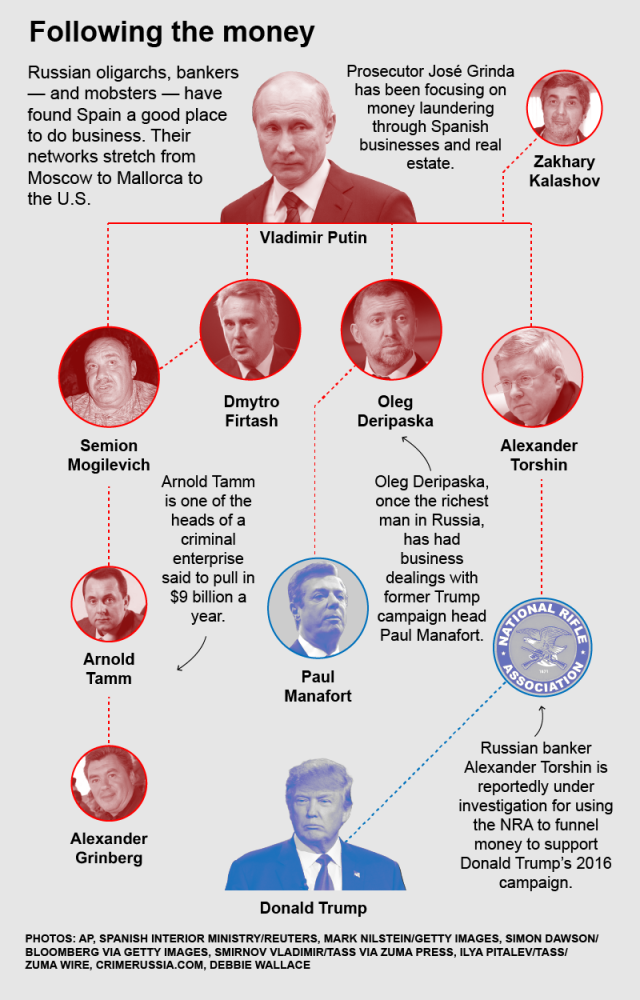

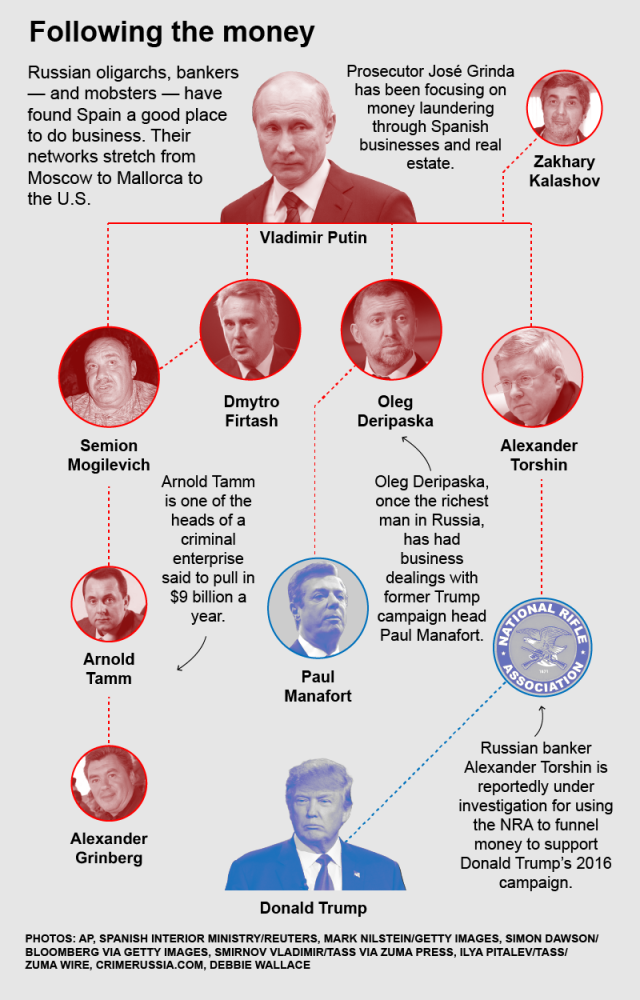

And it is where the work of Grinda overlaps with that of America’s Robert Mueller, the special counsel investigating allegations of Russian meddling in the 2016 election. Two of Mueller’s first four indictments, against former Trump campaign manager Paul Manafort and his associate Rick Gates, also a Trump campaign adviser, involve allegations of money laundering for a Russia-linked Ukrainian party. “You know where this is going,” Trump’s former close adviser Steve Bannon is quoted as saying in “Fire and Fury,” Michael Wolff’s explosive book about the Trump White House. “This is all about money laundering.”

Paul Manafort, President Trump’s former campaign chairman, departs federal district court in Washington in 2017. (Photo: Andrew Harnik/AP)

Paul Manafort, President Trump’s former campaign chairman, departs federal district court in Washington in 2017. (Photo: Andrew Harnik/AP)

Grinda’s investigations have targeted Russian banker Alexander Torshin, who has been described by Rep. Dana Rohrabacher, R-Calif., as “the conservatives’ favorite Russian.” Spanish authorities sought to arrest Torshin during a planned visit to Spain in 2013 on suspicion that he was laundering money through a Mallorca hotel that he secretly owned from afar; possibly tipped off, Torshin didn’t show in Spain, and Grinda says he’s no longer pursuing the case. But in the years since, Torshin has been making headlines in the U.S. He was scheduled to meet privately with President Trump at the National Prayer Breakfast in Washington last year, but the meeting was called off when someone in the administration flagged Torshin as a figure with “baggage.” (Torshin has strongly denied ties to Russian organized crime.) In November, news broke that Torshin had attempted to engineer a meeting between then-candidate Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin. And this week, McClatchy DC reported that the FBI is investigating whether Torshin donated money to financially support the Trump campaign in 2016, funneling his contributions through the National Rifle Association, which reported spending $30 million to back Trump. It is illegal for foreign nationals to give money to influence a U.S. election. The NRA did not respond to a request for comment.

Alexander Torshin (Photo: Shalgin Alexander/TASS via ZUMA Press)

Alexander Torshin (Photo: Shalgin Alexander/TASS via ZUMA Press)

With 12 years experience of doggedly pursuing crime syndicates, tapping their phones and unraveling their financial tentacles, Grinda — who learned some of the ropes from former Russian intelligence agent Alexander Litvinenko — is now world-famous as an anti-mafia crusader. And that’s a dangerous position to be in. Litvinenko, notoriously, was murdered in London just before he was supposed to meet with Spanish prosecutors to tell them what he knew about Russian mobsters. And Grinda himself, under round-the-clock police protection, has had to fend off accusations of child molestation that he denies and believes were invented by Russian criminals to discredit him.

Retired 25-year FBI veteran Marc Varri, who spent a decade as that agency’s legal attaché in Madrid, regards Grinda as a “very aggressive” prosecutor who maintains “a strong relationship with the U.S.” The Spaniard has been so much ahead in understanding the game that a few years ago the FBI embedded an agent to work with Grinda, hoping to untangle the network of Mogilevich. Because of Grinda, says Varri, “we were getting a better picture of what Russian organized crime was doing.”

In operations with names like Troika (named for three leaders of the Tambov gang), Avispa (wasp) or Variola (smallpox, alluding to the disease that left Mogilevich with his telltale scars), Grinda has gone after high-profile Russian mob figures, including some who have made headlines in the American press.

When asked how many Russian mobsters are now residing in Spain, Grinda shrugs with a wry smile. “Less than before.”

He’s imprisoned the likes of kingpin and arms runner Zakhary Kalashov, two weeks ago blacklisted by the FBI as a “crowned thief-in-law” — a VIP in the Russian criminal underworld — meaning that U.S. companies are prohibited from doing business with him and any American-held assets can be frozen. After eight years behind bars in Spain — and a 22 million euro fine — Kalashov was deported to Russia. Grinda has gone after the leaders of the Tambov gang, which was active in St. Petersburg in the 1990s, allegedly with the complicity of Putin, who was getting his start in politics in the mayor’s office.

Zakhar Kalashov, the alleged head of the Georgian mafia, is escorted on arrival at the Torrejon military air base outside Madrid in 2006. (Photo: Spanish Interior Ministry/Handout via Reuters)

Zakhar Kalashov, the alleged head of the Georgian mafia, is escorted on arrival at the Torrejon military air base outside Madrid in 2006. (Photo: Spanish Interior Ministry/Handout via Reuters)

Grinda and powerful Spanish judge Fernando Andreu flew to Moscow in 2010 to interrogate oligarch Oleg Deripaska, who two years earlier had been listed by Forbes as the richest man in Russia. Deripaska has had a long and complicated relationship with Manafort. He is suing the former Trump associate for $19 million over a business deal gone bad. Emails obtained by congressional investigators show Manafort offered the mogul private briefings on the 2016 presidential race.

Last year, Grinda and his team sent warrants to Austria to extradite Ukrainian billionaire Dmytro Firtash to Spain — again on money-laundering charges — activities that, oddly, came to light during a raid in Málaga when a mobster lawyer began literally eating a document, quickly retrieved from his mouth by police. Firtash made his fortune in the natural gas industry and, according to U.S. diplomatic cables posted by WikiLeaks, has admitted to fronting for Mogilevich. The businessman, who a decade ago partnered with Manafort in an unsuccessful effort to purchase a New York hotel, successfully fought extradition, but he is also being sought by the Department of Justice in a separate investigation involving allegations of bribery of government officials in India.

“The Russian mafia,” Grinda explains in his Madrid office — where shelves, dotted with a few Russian stacking dolls, are thick with boxed files with names like Ivanov and Petrov — “first appeared in Spain in the ’90s, after the fall of the Soviet Union.” Escape from Siberian winds wasn’t the sole impetus: “They weren’t just looking for sun, they were looking for anonymity.” And, he says, for quite a few years they found it. “Important mafiosos went to the Costa del Sol” — Marbella and environs — “and nobody bothered them there.” The police believed they were involved in criminal endeavors, says Grinda, but the legal system didn’t bother pursuing them or know exactly how to.

Ukrainian billionaire Dmytro Firtash in 2016. (Photo: Simon Dawson/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Ukrainian billionaire Dmytro Firtash in 2016. (Photo: Simon Dawson/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

That changed in 2004, when Grinda’s predecessor, David Martínez Madero, became intrigued with organized-crime activities — spending two years in Romania to learn about Russian and associated East European mobs, and concluding that their main endeavors in Spain were investing dirty money.

When Grinda took over the post as lead special prosecutor in 2006, he inherited a wealth of information from Martínez’s studies abroad. That year, Grinda also made contact with another expert on Russian organized crime, Litvinenko, a former Russian intelligence agent who’d fled to London a few years after Putin became president.

Grinda skirts many details of the collaboration, though he affirms that Litvinenko helped identify individuals and organizations active in Spain and that the intelligence agent had agreed to come to Spain in November 2006 to testify about the Russian mafia activities there. According to Litvinenko’s friend and fellow dissident Alex Goldfarb, president of the Litvinenko Justice Foundation, Litvinenko was planning to link Putin to the Spanish operations in his testimony.

Luke Harding, author of “A Very Expensive Poison,” writes that Litvinenko “was willing to testify in court against Putin … spilling everything he knew about Putin’s alleged links with the Tambov gang. … Enough reason for powerful people in Moscow to want Litvinenko silenced.” Litvinenko was also outspoken about Putin’s alleged links to Mogilevich, even making a taped statement about their warm relations in 2005.

The week before Litvinenko was to arrive in Madrid, he fell ill with radiation sickness; he died three weeks later, poisoned by a lethal dose of polonium. In 2016, the official British investigation into his death concluded that the Russian government was behind the poisoning, and noted that Litvinenko’s planned testimony in Spain may have played a role in his death.

Beyond providing Spain with invaluable information, Litvinenko inadvertently made Grinda famous. In 2010, WikiLeaks dumped FBI cables — including some from January of that year, in which Grinda is quoted extensively. A flurry of press kicked up, including a line attributed to Grinda saying that Russia is a “virtual mafia state.”

“I didn’t say that,” Grinda protests. “I said that was Litvinenko’s theory. And when Russia killed him, people believed he must have been correct.” The Kremlin and Duma didn’t appear squeaky clean when the man accused of carrying out the assassination of Litvinenko, Andrei Lugovoi, despite being wanted by the British police, launched a political career and was elected to the Russian parliament, becoming deputy head of the Duma Committee on Security and Corruption. While the British inquiry into Litvinenko’s poisoning was ongoing, Putin presented him with an award honoring his “service to the motherland.”

The grave of murdered ex-KGB agent Alexander Litvinenko at Highgate Cemetery in London. (Photo: Toby Melville/Reuters)

The grave of murdered ex-KGB agent Alexander Litvinenko at Highgate Cemetery in London. (Photo: Toby Melville/Reuters)

Even if he didn’t call Russia a “mafia state,” Grinda believes that organized crime is deeply entangled in Russia’s government.

Others underscore the nexus between the Kremlin and the Russian organized-crime groups working in Spain and across Europe, as well as in the U.S.

“It started,” says mafia expert Walter Kegö of the Institute for Security and Development Policy in Stockholm, “when Putin was deputy mayor of St. Petersburg and used mafia groups to buy property and launder money.” And in the years since Putin rose to president of Russia, he says, it’s continued. Kegö believes the majority of the mafias’ money-making activities take place in Russia and Eastern Europe, but they turn to “Spain, the U.S., Israel, the U.K., and the rest of Europe” to invest it and clean it up. “We’re talking a lot of money, a lot of billions,” he adds.

Louise Shelley, an organized-crime expert who founded and directs the Terrorism, Transnational Crime and Corruption Center at George Mason University, sees the connection between the Russian mafia and Moscow’s government, too. “In the 1990s,” says the author of “Dirty Entanglements: Crime, Corruption, and Terrorism,” American intelligence agencies’ wiretaps picked up “direct calls from Russian organized-crime [members] in the U.S. to the Kremlin.”

And whether in Spain, the U.S. or the U.K., one of the easiest ways to launder criminal gains is buying real estate, says Shelley, who’s written on the matter for decades. “It’s a major problem. So much organized-crime money has been successfully moved into the U.S.”

In Spain, that may translate into beachside hotels or cliff-perched villas, but in the United State that often means luxury apartments in high-rent cities. Say, for instance, Trump properties from Manhattan to Miami: In New York’s Trump Tower, which served as campaign headquarters, at least one Mogilevich lackey — David Bogatin — purchased five apartments in 1984, according to Craig Unger, who wrote about money laundering through Trump real estate for the New Republic. And, says Shelley, it hasn’t stopped since.

“It appears there’s lots of organized crime and kleptocratic corruption moving into Trump properties,” she says.

Trump Tower in New York City. (Photo: Mike Segar/Reuters)

Trump Tower in New York City. (Photo: Mike Segar/Reuters)

According to a recent article in BuzzFeed News, some “$1.5 billion in secretive sales” — using anonymous buyers and shell corporations — was documented in Trump properties, some owned by the president’s companies, some that just used his name under license. According to BuzzFeed, in the Trump Hollywood building alone 43 percent of the units, sold for $136 million, “were sales with signs of possible money laundering.”

“They like high-end properties,” Shelley says, “and they’re not asked as many questions” when dealing with Trump. “Trump has been known to the Russian community for a long time. … He’s been traveling there for decades,” she adds.

Which raises the question of why these purchases haven’t rung alarm bells in the U.S., the way they have in Spain. The reason goes back more than 16 years, Shelley believes, to the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. “The U.S. was very good on post-Soviet organized crime in the 1990s,” she says. After Sept. 11, 2001, however, “all that capacity was closed down and transferred to terrorism.” Since 9/11, she says the U.S. has “not been working on post-Soviet organized crime in any cohesive way, and that’s what we’re seeing consequences of today.”

With a new U.S. national security program that again targets transnational crime, including money laundering, that may be changing. In the battle against Russian criminal organizations, “Spain has been an important piece,” she says. “Spain has been on it continuously.”

Grinda “is doing a tremendous job,” says Kegö, adding that Spain is by far the most relentless European country in going after organized crime. “No question about that,” he says, wondering, as does Shelley, why Britain, where laundered money is pouring into real estate, hasn’t joined in.

José Grinda at the Generalitat in Barcelona in 2017. (Photo: Pau Barrena /AFP/Getty Images)

José Grinda at the Generalitat in Barcelona in 2017. (Photo: Pau Barrena /AFP/Getty Images)

Grinda, who works with authorities in Italy, France and Germany, wonders the same. He says his team gets “zero” cooperation from the British regarding Russian organized crime.

Another mafia expert, author and investigative reporter Roberto Saviano, speculates that Britain itself, a mecca for Russian billionaires — and where the BBC show “McMafia,” about Russian mobsters, is a huge hit — has become the most corrupt place on the planet. “It’s not U.K. bureaucracy, police or politics,” he said in a 2016 speech, “but what is corrupt is the financial capital. Ninety percent of the owners of capital in London have their headquarters offshore. … Jersey and the Caymans are the access gates to criminal capital in Europe, and the U.K. is the country that allows it.”

Grinda is not sure of the reasons. But he does have a theory about how the Russian mafia works. “Unlike terrorists, they don’t want to destroy the political structure,” he says. “They want to work within it” — corrupting and corroding it from within.

Take, for instance, what a 2013 operation revealed in Lloret de Mar, a fetching coastal city in Catalonia, the region in northeastern Spain that is now involved in a struggle with the central government over secession. When a Russian mobster launched a construction company there, he patronized the soccer and hockey teams and donated massive amounts to restore the city soccer field. He allegedly spread bribes liberally among the local officials in exchange for favors including approval for a mall he wanted to build and reduced taxes, and set up an operation that laundered some 50 million euros believed to have originated in Moscow. After waiting two years behind bars, the Russian, Andrei Petrov, was released after paying a 450,000 euro fine and spilling the beans on his operations to the judge.

Andrei Petrov arrives at the courthouse in Barcelona in 2015. (Photo: Lola Bou)

Andrei Petrov arrives at the courthouse in Barcelona in 2015. (Photo: Lola Bou)

Similarly, back in Marbella, Alexander Grinberg made himself a local hero when he swooped in to save the beleaguered soccer team — buying it for one euro in 2013, paying off its $300,000 debt and pumping bushels more cash into it to recruit new players and advance the team into the professional second division.

Like real estate, Grinda says, sports teams are excellent ways to obscure the origins of ill-gotten money. Owning a sports team, he adds, “has a second benefit. It enhances the owner’s reputation” — allowing influence and entry into the world of civic leaders and politicians, even banks. That, he believes, based on intercepted phone calls, is one of the Russian mafia’s goals in Spain.

Wiretapping is essential to Grinda’s team’s investigations, and in addition to chatter about bank transfers and installing cameras to spy on partners in Russian-owned gyms, they’ve revealed charm offensives — like buying perfume for the women employees of the local bank — as well as Soprano-esque woes about health and who’s hitting the sauce too much.

Ordering the arrests and trials of hundreds of those affiliated with Russian mafias — a group that also spills into Ukraine, Georgia, Estonia, Armenia and beyond — Grinda’s raids are causing backlash. Despite the prosecutor’s unflappable exterior, he’s taken heat for it. Last year, police in France intercepted a phone call from a Georgian mafia member ordering a hit on Grinda; he now has four bodyguards and 24/7 protection for his family.

Last year, when Grinda and his fellow prosecutor Juan Carrau sent off a 488-page report to Moscow’s head prosecutor, naming more names of Russian officials and detailing their suspected criminal activities, there was retaliation. Not only did the Moscow prosecutor do nothing with the information, but soon thereafter a Spanish lawyer began accusing Grinda of being a pedophile, a story picked up exclusively by questionable internet sites in Spain.

Russian magnate Alexander Grinberg (left), as the Guardia Civil performs a raid on his Marbella yacht on Sept. 26, 2017. (Photo: G Tres Informacion Mas Comunicacion On Line, S.L./Alamy Live News)

Russian magnate Alexander Grinberg (left), as the Guardia Civil performs a raid on his Marbella yacht on Sept. 26, 2017. (Photo: G Tres Informacion Mas Comunicacion On Line, S.L./Alamy Live News)

“I have a witness who says that [a former Kremlin cabinet member] paid the lawyer to say that,” says Grinda. The Spanish lawyer, he adds, was terminally ill, and Grinda believes he took the handsome payoff to provide security for his family. (The lawyer died in September.) Grinda is pursuing a defamation case, and until the matter is cleared up in the courts, an internet search of his name brings up hundreds of dubious articles about the special prosecutor being a child molester.

He shrugs, implying it’s just one of the hazards of the job — a job he never imagined he would find himself in, expecting a career as a run-of-the-mill state prosecutor. And his efforts are making a difference, perhaps even shaking up things in Russia, according to Mark Galeotti of the European Council on Foreign Relations. “Spain is becoming increasingly ambitious and aggressive in its investigation of [Russian] crime networks,” wrote Galeotti, noting that a Spanish judge issued a request for “international arrest warrants” for several senior Russian officials for alleged involvement in Russian mafia groups. “The Spanish courts are, deliberately or not, embarking on an audacious campaign to use an investigation of crimes in their own country to begin a fight back against the criminalization of Russian politics.”

Grinda takes it in stride. “We can do what we do because Spain isn’t so important politically in the world,” he says. His department has ample resources, and “we don’t have big business standing in our way.” And his work is paying off: “The grand mafia personages don’t come here anymore” — though they still try to do business in Spain — and, while he has no exact numbers, he’s certain that Russian mafia activity is “less, a lot less” than it was even a decade ago.

The message he wants to get out to the Russian mob is simple: “Don’t come to Spain. And don’t think you can camouflage your business activities here.”

When asked if he sees similarities between his job and that of Robert Mueller, he laughs. “No, I am not the Robert Mueller of Spain. But [like Mueller], I have a great team.”

_____

Melissa Rossi, a writer based in Spain, is the author of the geopolitical series “What Every American Should Know” (Plume/Penguin). Additional reporting by Michael Isikoff and Hunter Walker.

Above is from: https://www.yahoo.com/news/spains-robert-mueller-takes-russian-mob-202248019.html

uadra (Catalan regional police officer) salutes Spanish anti-corruption prosecutor José Grinda, center, as he leaves the Generalitat de Catalunya (Catalan government) in Barcelona in 2017. (Photo: Pau Barrena/AFP/Getty Images)

uadra (Catalan regional police officer) salutes Spanish anti-corruption prosecutor José Grinda, center, as he leaves the Generalitat de Catalunya (Catalan government) in Barcelona in 2017. (Photo: Pau Barrena/AFP/Getty Images)  Alexander Grinberg (Photo: Debbie Wallace)

Alexander Grinberg (Photo: Debbie Wallace)

Paul Manafort, President Trump’s former campaign chairman, departs federal district court in Washington in 2017. (Photo: Andrew Harnik/AP)

Paul Manafort, President Trump’s former campaign chairman, departs federal district court in Washington in 2017. (Photo: Andrew Harnik/AP)  Alexander Torshin (Photo: Shalgin Alexander/TASS via ZUMA Press)

Alexander Torshin (Photo: Shalgin Alexander/TASS via ZUMA Press)  Zakhar Kalashov, the alleged head of the Georgian mafia, is escorted on arrival at the Torrejon military air base outside Madrid in 2006. (Photo: Spanish Interior Ministry/Handout via Reuters)

Zakhar Kalashov, the alleged head of the Georgian mafia, is escorted on arrival at the Torrejon military air base outside Madrid in 2006. (Photo: Spanish Interior Ministry/Handout via Reuters)  Ukrainian billionaire Dmytro Firtash in 2016. (Photo: Simon Dawson/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Ukrainian billionaire Dmytro Firtash in 2016. (Photo: Simon Dawson/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

The grave of murdered ex-KGB agent Alexander Litvinenko at Highgate Cemetery in London. (Photo: Toby Melville/Reuters)

The grave of murdered ex-KGB agent Alexander Litvinenko at Highgate Cemetery in London. (Photo: Toby Melville/Reuters)  Trump Tower in New York City. (Photo: Mike Segar/Reuters)

Trump Tower in New York City. (Photo: Mike Segar/Reuters)  José Grinda at the Generalitat in Barcelona in 2017. (Photo: Pau Barrena /AFP/Getty Images)

José Grinda at the Generalitat in Barcelona in 2017. (Photo: Pau Barrena /AFP/Getty Images)  Andrei Petrov arrives at the courthouse in Barcelona in 2015. (Photo: Lola Bou)

Andrei Petrov arrives at the courthouse in Barcelona in 2015. (Photo: Lola Bou)  Russian magnate Alexander Grinberg (left), as the Guardia Civil performs a raid on his Marbella yacht on Sept. 26, 2017. (Photo: G Tres Informacion Mas Comunicacion On Line, S.L./Alamy Live News)

Russian magnate Alexander Grinberg (left), as the Guardia Civil performs a raid on his Marbella yacht on Sept. 26, 2017. (Photo: G Tres Informacion Mas Comunicacion On Line, S.L./Alamy Live News)