Vanessa Solivan and her three children fled their last place in June 2015, after a young man was shot and killed around the corner. They found a floor to sleep on in Vanessa’s parents’ home on North Clinton Avenue in East Trenton. It wasn’t a safer neighborhood, but it was a known one. Vanessa took only what she could cram into her station wagon, a 2004 Chrysler Pacifica, letting the bed bugs have the rest.

At her childhood home, Vanessa began caring for her ailing father. He had been a functional crack addict for most of her life, working as a landscaper in the warmer months and collecting unemployment when business slowed down. “It was something you got used to seeing,” Vanessa said about her father’s drug habit. “My dad was a junkie, but he never left us.” Vanessa, 33, has black hair that is usually pulled into a bun and wire-framed glasses that slide down her nose; a shy smile peeks out when she feels proud of herself.

Vanessa’s father died a year after Vanessa moved in. The family erected a shrine to him in the living room, a faded, large photo of a younger man surrounded by silk flowers and slowly sinking balloons. Vanessa’s mother, Zaida, is 62 and from Puerto Rico, as was her husband. She uses a walker to get around. Her husband’s death left her with little income, and Vanessa was often broke herself. Her health failing, Zaida could take only so much of Vanessa’s children, Taliya, 17, Shamal, 14, and Tatiyana, 12. When things got too loud or one of her grandchildren gave her lip, she would ask Vanessa to take her children somewhere else.

If Vanessa had the money, or if a local nonprofit did, she would book a motel room. She liked the Red Roof Inn, which she saw as “more civilized” than many of the other motels she had stayed in. It looked like a highway motel: two stories with doors that opened to the outside. The last time the family checked in, the kids carried their homework up to the room as Vanessa followed with small grocery bags from the food pantry, passing two men sipping Modelos and apologizing for their loud music. Inside their room, Vanessa placed her insulin in the minifridge as her children chose beds, where they would sleep two to a mattress. Then she slid into a small chair, saying, “Y’all don’t know how tired Mommy is.” After a quiet moment, Vanessa reached over and rubbed Shamal’s back, telling him, “I wish we had a nice place like this.” Then her eye spotted a roach feeling its way over the stucco wall.

“Op! Not too nice,” Vanessa said, grinning. With a flick, she sent the bug flying toward Taliya, who squealed and jerked back. Laughter burst from the room.

When Vanessa couldn’t get a motel, the family spent the night in the Chrysler. The back of the station wagon held the essentials: pillows and blankets, combs and toothbrushes, extra clothes, jackets and nonperishable food. But there were also wrinkled photos of her kids. One showed Taliya at her eighth-grade graduation in a cream dress holding flowers. Another showed all three children at a quinceañera — Shamal kneeling in front, with a powder blue clip-on bow tie framing his baby face, and Tatiyana tucked in back with a deep-dimpled smile.

Image

Vanessa Solivan at her mother’s house with Tatiyana and Shamal.CreditDevin Yalkin for The New York Times

So that the kids wouldn’t run away out of anger or shame, Vanessa learned to park off Route 1, in crevices of the city that were so still and abandoned that no one dared crack a door until daybreak. Come morning, Vanessa would drive to her mother’s home so the kids could get ready for school and she could get ready for work.

In May, Vanessa finally secured a spot in public housing. But for almost three years, she had belonged to the “working homeless,” a now-necessary phrase in today’s low-wage/high-rent society. She is a home health aide, the same job her mother had until her knees and back gave out. Her work uniform is Betty Boop scrubs, sneakers and an ID badge that hangs on a red Bayada Home Healthcare lanyard. Vanessa works steady hours and likes her job, even the tougher bits like bathing the infirm or hoisting someone out of bed with a Hoyer lift. “I get to help people,” she said, “and be around older people and learn a lot of stuff from them.” Her rate fluctuates: She gets $10 an hour for one client, $14 for another. It doesn’t have to do with the nature of the work — “Sometimes the hardest ones can be the cheapest ones,” Vanessa said — but with reimbursement rates, which differ according to the client’s health care coverage. After juggling the kids and managing her diabetes, Vanessa is able to work 20 to 30 hours a week, which earns her around $1,200 a month. And that’s when things go well.

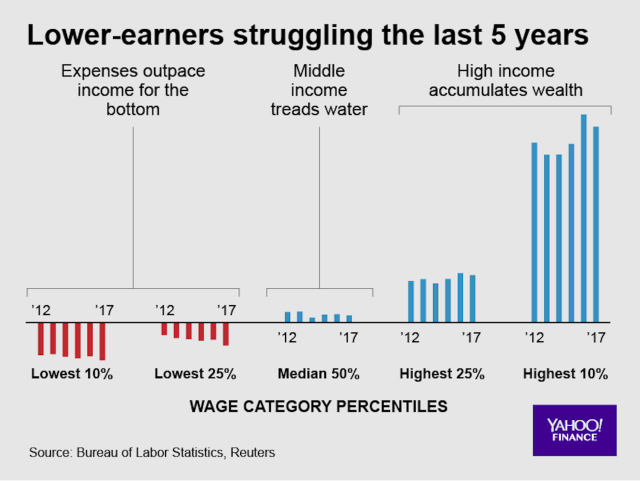

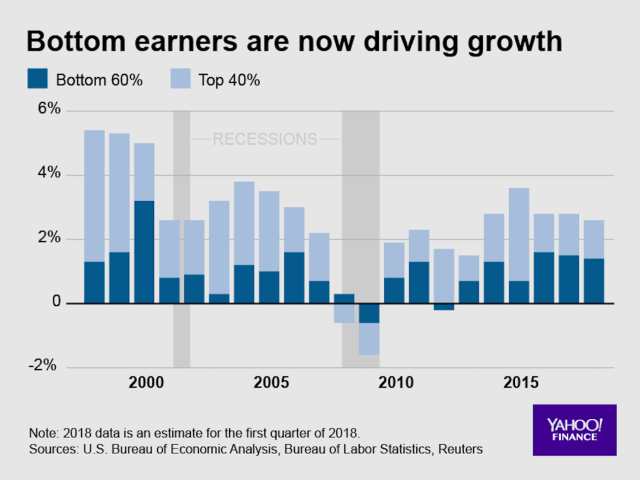

These days, we’re told that the American economy is strong. Unemployment is down, the Dow Jones industrial average is north of 25,000 and millions of jobs are going unfilled. But for people like Vanessa, the question is not, Can I land a job? (The answer is almost certainly, Yes, you can.) Instead the question is, What kinds of jobs are available to people without much education? By and large, the answer is: jobs that do not pay enough to live on.

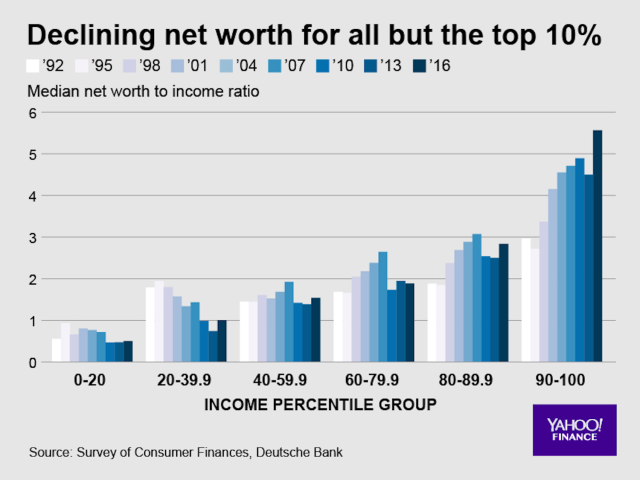

In recent decades, the nation’s tremendous economic growth has not led to broad social uplift. Economists call it the “productivity-pay gap” — the fact that over the last 40 years, the economy has expanded and corporate profits have risen, but real wages have remained flat for workers without a college education. Since 1973, American productivity has increased by 77 percent, while hourly pay has grown by only 12 percent. If the federal minimum wage tracked productivity, it would be more than $20 an hour, not today’s poverty wage of $7.25.

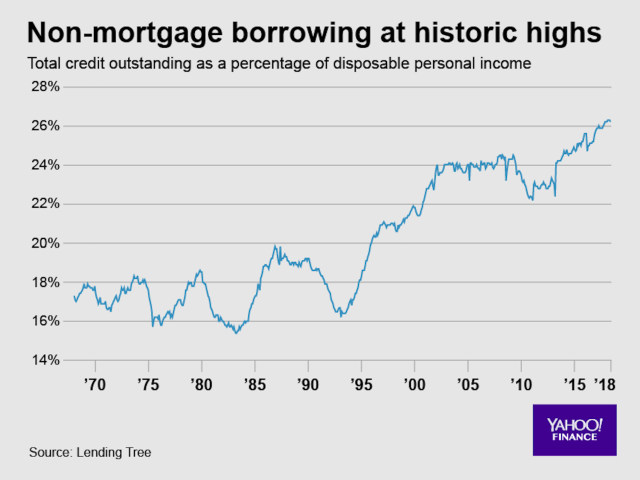

American workers are being shut out of the profits they are helping to generate. The decline of unions is a big reason. During the 20th century, inequality in America decreased when unionization increased, but economic transformations and political attacks have crippled organized labor, emboldening corporate interests and disempowering the rank and file. This imbalanced economy explains why America’s poverty rate has remained consistent over the past several decades, even as per capita welfare spending has increased. It’s not that safety-net programs don’t help; on the contrary, they lift millions of families above the poverty line each year. But one of the most effective antipoverty solutions is a decent-paying job, and those have become scarce for people like Vanessa. Today, 41.7 million laborers — nearly a third of the American work force — earn less than $12 an hour, and almost none of their employers offer health insurance.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics defines a “working poor” person as someone below the poverty line who spent at least half the year either working or looking for employment. In 2016, there were roughly 7.6 million Americans who fell into this category. Most working poor people are over 35, while fewer than five in 100 are between the ages of 16 and 19. In other words, the working poor are not primarily teenagers bagging groceries or scooping ice cream in paper hats. They are adults — and often parents — wiping down hotel showers and toilets, taking food orders and bussing tables, eviscerating chickens at meat-processing plants, minding children at 24-hour day care centers, picking berries, emptying trash cans, stacking grocery shelves at midnight, driving taxis and Ubers, answering customer-service hotlines, smoothing hot asphalt on freeways, teaching community-college students as adjunct professors and, yes, bagging groceries and scooping ice cream in paper hats.

America prides itself on being the country of economic mobility, a place where your station in life is limited only by your ambition and grit. But changes in the labor market have shrunk the already slim odds of launching yourself from the mailroom to the boardroom. For one, the job market has bifurcated, increasing the distance between good and bad jobs. Working harder and longer will not translate into a promotion if employers pull up the ladders and offer supervisory positions exclusively to people with college degrees. Because large companies now farm out many positions to independent contractors, those who buff the floors at Microsoft or wash the sheets at the Sheraton typically are not employed by Microsoft or Sheraton, thwarting any hope of advancing within the company. Plus, working harder and longer often isn’t even an option for those at the mercy of an unpredictable schedule. Nearly 40 percent of full-time hourly workers know their work schedules just a week or less in advance. And if you give it your all in a job you can land with a high-school diploma (or less), that job might not exist for very long: Half of all new positions are eliminated within the first year. According to the labor sociologist Arne Kalleberg, permanent terminations have become “a basic component of employers’ restructuring strategies.”

Home health care has emerged as an archetypal job in this new, low-pay service economy. Demand for home health care has surged as the population has aged, but according to the latest data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the 2017 median annual income for home health aides in the United States was just $23,130. Half of these workers depend on public assistance to make ends meet. Vanessa formed a rapport with several of her clients, to whom she confided that she was homeless. One replied, “Oh, Vanessa, I wish I could do something for you.” When Vanessa told her supervisor about her situation, he asked if she wanted time off. “No!” Vanessa said. She needed the money and had been picking up fill-in shifts. The supervisor was prepared for the moment; he’d been there before. He reached into a drawer and gave her a $50 gas card to Shell and a $100 grocery card to ShopRite. Vanessa was grateful for the help. She thought Bayada was a generous and sympathetic employer, but her rate hadn’t changed much in the three years she had worked there. Vanessa earned $9,815.75 in 2015, $12,763.94 in 2016 and $10,446.81 last year.

To afford basic necessities, the federal government estimates that Vanessa’s family would need to bring in $29,420 a year. Vanessa is not even close — and she is one of the lucky ones, at least among the poor. The nation’s safety net now strongly favors the employed, with benefits like the earned-income tax credit, a once-a-year cash boost that applies only to people who work. Last year, Vanessa received a tax return of around $5,000, which included earned-income and child tax credits. They helped raise her income, but not above the poverty line. If the working poor are doing better than the nonworking poor, which is the case, it’s not so much because of their jobs per se, but because their employment status provides them access to desperately needed government help. This has caused growing inequality below the poverty line, with the working poor receiving much more social aid than the abandoned nonworking poor or the precariously employed, who are plunged into destitution.

When life feels especially grinding, Vanessa often rings up Sheri Sprouse, her best friend since middle school. “She’s like me,” Vanessa said. “She’s strong.” Sheri is a reserve of emotional support and perspective, often encouraging her friend to be patient and grateful for what she has. But Sheri herself is also just scraping by, raising two daughters on a fixed disability check. And because Sheri’s housing is subsidized through a federally administered voucher, it is also monitored. “With Section 8, you can’t have people staying with you,” Vanessa said. “So I wouldn’t want to mess that up.” When Vanessa was homeless, Sheri couldn’t offer her much else besides love.

Vanessa received some help last year, when her youngest child, Tatiyana, was approved for Supplemental Security Income because of a learning disability. Vanessa began receiving a monthly $766 disability check. But when the Mercer County Board of Social Services learned of this additional money, it sent Vanessa a letter announcing that her Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits would be reduced to $234 from $544. Food was a constant struggle, and this news didn’t help. A 2013 study by Oxfam America found that two-thirds of working poor people worry about being able to afford enough food. When Vanessa stayed at a hotel, her food options were limited to what she could heat in the microwave; when she slept in her car, the family had to settle for grab-and-go options, which tend to be more expensive. Sometimes Vanessa stopped by a bodega and ordered four chicken-and-rice dishes for $15. Sometimes her kids went to school hungry. “I just didn’t have nothing,” Vanessa told me one morning. For dinner, she planned to stop by a food pantry, hoping they still had the mac-and-cheese that Shamal liked.

In America, if you work hard, you will succeed. So those who do not succeed have not worked hard. It’s an idea found deep in the marrow of the nation. William Byrd, an 18th-century Virginia planter, wrote of poor men who were “intolerable lazy” and “Sloathful in everything but getting of Children.” Thomas Jefferson advocated confinement in poorhouses for vagabonds who “waste their time in idle and dissolute courses.” Leap into the 20th century, and there’s Barry Goldwater saying that Americans with little education exhibit “low intelligence or low ambition” and Ronald Reagan disparaging “welfare queens.” In 2004, Bill O’Reilly said of poor people: “You gotta look people in the eye and tell ’em they’re irresponsible and lazy,” and then continued, “Because that’s what poverty is, ladies and gentlemen.”

Americans often assume that the poor do not work. According to a 2016 survey conducted by the American Enterprise Institute, nearly two-thirds of respondents did not think most poor people held a steady job; in reality, that year a majority of nondisabled working-age adults were part of the labor force. Slightly over one-third of respondents in the survey believed that most welfare recipients would prefer to stay on welfare rather than earn a living. These sorts of assumptions about the poor are an American phenomenon. A 2013 study by the sociologist Ofer Sharone found that unemployed workers in the United States blame themselves, while unemployed workers in Israel blame the hiring system. When Americans see a homeless man cocooned in blankets, we often wonder how he failed. When the French see the same man, they wonder how the state failed him.

If you believe that people are poor because they are not working, then the solution is not to make work pay but to make the poor work — to force them to clock in somewhere, anywhere, and log as many hours as they can. But consider Vanessa. Her story is emblematic of a larger problem: the fact that millions of Americans work with little hope of finding security and comfort. In recent decades, America has witnessed the rise of bad jobs offering low pay, no benefits and little certainty. When it comes to poverty, a willingness to work is not the problem, and work itself is no longer the solution.

Image

Vanessa in the living room of her mother’s house with Tatiyana.CreditDevin Yalkin for The New York Times

Until the late 18th century, poverty in the West was considered not only durable but desirable for economic growth. Mercantilism, the dominant economic theory of the early modern period, held that hunger incentivized work and kept wages low. Wards of public charity were jailed and required to work to eat. In the current era, politicians and their publics have continued to demand toil and sweat from the poor. In the 1980s, conservatives wanted to attach work requirements to food stamps. In the 1990s, they wanted to impose work requirements on subsidized-housing programs. Both proposals failed, but the impulse has endured.

Advocates of work requirements scored a landmark victory with welfare reform in the mid-1990s. Proposed by House Republicans, led by Speaker Newt Gingrich, and signed into law by President Bill Clinton, welfare reform affixed work requirements and time limits to cash assistance. Caseloads fell to 4.5 million in 2011 from 12.3 million in 1996. Did “welfare to work” in fact work? Was it a major success in reducing poverty and sowing prosperity? Hardly. As Kathryn Edin and Laura Lein showed in their landmark book, “Making Ends Meet,” single mothers pushed into the low-wage labor market earned more money than they did on welfare, but they also incurred more expenses, like transportation and child care, which nullified modest income gains. Most troubling, without guaranteed cash assistance for the most needy, extreme poverty in America surged. The number of Americans living on only $2 or less per person per day has more than doubled since welfare reform. Roughly three million children — which exceeds the population of Chicago — now suffer under these conditions. Most of those children live with an adult who held a job sometime during the year.

A top priority for the Trump administration is expanding work requirements for some of the nation’s biggest safety-net programs. In January, the federal government announced that it would let states require that Medicaid recipients work. A dozen states have formally applied for a federal waiver to affix work requirements to their Medicaid programs. Four have been approved. In June, Arkansas became the first to implement newly approved work requirements. If all states instated Medicaid work requirements similar to that of Arkansas, as many as four million Americans could lose their health insurance.

In April, President Trump issued an executive order mandating that federal agencies review welfare programs, from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program to housing assistance, and propose new standards. Although SNAP already has work requirements, in June the House passed a draft farm bill that would deny able-bodied adults SNAP benefits for an entire year if they did not work or engage in work-related activities (like job training) for at least 20 hours a week during a single month. Falling short a second time could get you barred for three years. The Senate’s farm bill, a bipartisan effort, removed these rules and stringent penalties, setting up a showdown with the House, whose version Trump has endorsed. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that work requirements could deny 1.2 million people a benefit that they use to eat.

Work requirements affixed to other programs make similar demands. Kentucky’s proposed Medicaid requirements are satisfied only after 80 hours of work or work-related training each month. In a low-wage labor market characterized by fluctuating hours, tenuous employment and involuntary part-time work, a large share of vulnerable workers fall short of these requirements. Nationally representative data from the Survey of Income and Program Participation show that among workers who qualify for Medicaid, almost 50 percent logged fewer than 80 hours in at least one month.

In July, the White House Council of Economic Advisers issued a report enthusiastically endorsing work requirements for the nation’s largest welfare programs. The council favored “negative incentives,” tying aid to labor-market effort, and dismissed “positive incentives,” like tax benefits for low-income workers, because the former is cheaper. The council also claimed that America’s welfare policies have brought about a “decline in self-sufficiency.”

Is that true? Researchers set out to study welfare dependency in the 1980s and 1990s, when this issue dominated public debate. They didn’t find much evidence of it. Most people started using cash welfare after a divorce or separation and didn’t stay long on the dole, even if they returned to welfare periodically. One study found that 90 percent of young women on welfare stopped relying on it within two years of starting the program, but most of them returned to welfare sometime down the road. Even at its peak, welfare did not function as a dependency trap for a majority of recipients; rather, it was something people relied on when they were between jobs or after a family crisis. A 1988 review in Science concluded that “the welfare system does not foster reliance on welfare so much as it acts as insurance against temporary misfortune.”

Image

Vanessa and her client Laura at Laura’s home in Hamilton, N.J.CreditDevin Yalkin for The New York Times

Today as then, the able-bodied, poor and idle adult remains a rare creature. According to the Brookings Institution, in 2016 one-third of those living in poverty were children, 11 percent were elderly and 24 percent were working-age adults (18 to 64) in the labor force, working or seeking work. The majority of working-age poor people connected to the labor market were part-time workers. Most couldn’t take on many more hours either because of caregiver responsibilities, as with Vanessa, or because their employer didn’t offer this option, rendering them involuntary part-time workers. Among the remaining working-age adults, 12 percent were out of the labor force owing to a disability (including some enrolled in federal programs that limit work), 15 percent were either students or caregivers and 3 percent were early retirees. That leaves 2 percent of poor people who did not fit into one of these categories. That is, among the poor, two in 100 are working-age adults disconnected from the labor market for unknown reasons. The nonworking poor person getting something for nothing is a lot like the cheat committing voter fraud: pariahs who loom far larger in the American imagination than in real life.

When Vanessa was not working for Bayada, she was running after her kids. Vanessa worried over Shamal the most. At more than six feet tall, his size made him both a tool and a target in the neighborhood. Smaller kids wanted him to be their enforcer or trouble-starter. Harder kids saw him as a threat. Last year, Shamal was suspended twice for fighting. As punishment, Vanessa made him shave off his prized Afro. But she also set her children’s outbursts against a larger backdrop. “How’s their behavior supposed to be when we’re out here on these streets?” she asked me in frustration. Shamal once told me that outsiders “probably think I’m selling drugs. But I’m not. I’m just a cool person that likes hanging out and making people laugh.” He wanted to become a chef. Vanessa wondered if she could get Shamal a police-issued ankle bracelet, which would track his movements. It was impossible, of course, but Shamal liked the idea. “It could help me when my friends want me to go somewhere,” he told me. That is, the bracelet would give him a good excuse to back down when his friends nudged him toward a risky path.

Shamal and Tatiyana’s father had recently moved back to Trenton, “carrying a sack like a hobo,” Vanessa remembered. Other than erratic child-support payments and a single trip to Chuck E. Cheese’s, he doesn’t play much of a role in his children’s lives. Taliya’s father went to prison when she was 1. He was released when she was 8 and was killed a few months later, shot in the chest. Sometimes Vanessa’s three kids teased one another about their fathers. “Your dad is dead,” Tatiyana would say. “Yeah? Your dad’s around, but he don’t give a crap about you,” Taliya would shoot back.

Other times, though, the siblings offered soft reassurances that their fathers’ absence wasn’t their fault. “I don’t have time for him,” Tatiyana said once, as if it were her choice. “I have time for my real friends.” Taliya looked at her baby sister and replied: “Watch. When you’re doing good, he gonna start coming around.”

If Vanessa clocked more hours, it would be difficult to keep up with all the ways she manages her family: doing the laundry, arranging dentist appointments, counseling the children about sex, studying their deep mysteries to extract their gifts and troubles. Yet our political leaders tend to refuse to view child care as work. During the early days of welfare reform, some local authorities thought up useless jobs for single mothers receiving the benefit. In one outrageous case, recipients were made to sort small plastic toys into different colors, only to have their supervisor end the day by mixing everything up, so the work could start anew the next morning. This was thought more important than keeping children safe and fed.

Caring for a sick or dying parent doesn’t count either. Vanessa spooned arroz con gandules into her ailing father’s mouth, refilled his medications and emptied his bedpan. But only when she does these things for virtual strangers, as a Bayada employee, does she “work” and therefore become worthy of concern. As Evelyn Nakano Glenn argues in her 2010 book, “Forced to Care,” industrialization caused American families to become increasingly reliant on wages, which had the effect of reducing tasks that usually fell to women (homemaking, cooking, child care) to “moral and spiritual vocations.” “In contrast to men’s paid labor,” Glenn writes, “women’s unpaid caring was simultaneously priceless and worthless — that is, not monetized.” She continues: “To add insult to injury, because they could not live up to the ideal of full-time motherhood, poor women of color were seen as deficient mothers and caregivers.”

Vanessa attributed her own academic setbacks — a good student in middle school, she began cutting class and courting trouble in high school — to the fact that her parents were checked out. At a critical juncture when Vanessa needed guidance and discipline, her father was using drugs and her mother seemed always to be at work. She didn’t want to make the same mistake with her kids. Vanessa’s life revolved around a small routine: drop the kids off at school; work; try finding an apartment that rents for less than $1,000 a month; pick the kids up; feed them; sleep. She didn’t spend her money on extras, including cigarettes and alcohol. She was trying to save “the little money that I got,” she told me, “so when we do get a place, I can get the kids washcloths and towels.”

Image

Vanessa and Laura going to buy groceries.CreditDevin Yalkin for The New York Times

We might think that the existence of millions of working poor Americans like Vanessa would cause us to question the notion that indolence and poverty go hand in hand. But no. While other inequality-justifying myths have withered under the force of collective rebuke, we cling to this devastatingly effective formula. Most of us lack a confident account for increasing political polarization, rising prescription drug costs, urban sprawl or any number of social ills. But ask us why the poor are poor, and we have a response quick at the ready, grasping for this palliative of explanation. We have to, or else the national shame would be too much to bear. How can a country with such a high poverty rate — higher than those in Latvia, Greece, Poland, Ireland and all other member countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development — lay claim to being the greatest on earth? Vanessa’s presence is a judgment. But rather than hold itself accountable, America reverses roles by blaming the poor for their own miseries.

Here is the blueprint. First, valorize work as the ticket out of poverty, and debase caregiving as not work. Look at a single mother without a formal job, and say she is not working; spot one working part time and demand she work more. Transform love into laziness. Next, force the poor to log more hours in a labor market that treats them as expendables. Rest assured that you can pay them little and deny them sick time and health insurance because the American taxpayer will step in, subsidizing programs like the earned-income tax credit and food stamps on which your work force will rely. Watch welfare spending increase while the poverty rate stagnates because, well, you are hoarding profits. When that happens, skirt responsibility by blaming the safety net itself. From there, politicians will invent new ways of denying families relief, like slapping unrealistic work requirements on aid for the poor.

Democrats may scoff at Republicans’ work requirements, but they have yet to challenge the dominant conception of poverty that feeds such meanspirited politics. Instead of offering a counternarrative to America’s moral trope of deservedness, liberals have generally submitted to it, perhaps even embraced it, figuring that the public will not support aid that doesn’t demand that the poor subject themselves to the low-paying jobs now available to them. Even stalwarts of the progressive movement seem to reserve economic prosperity for the full-time worker. Senator Bernie Sanders once declared, echoing a long line of Democrats who have come before and after him, “Nobody who works 40 hours a week should be living in poverty.” Sure, but what about those who work 20 or 30 hours, like Vanessa?

Because liberals have allowed conservatives to set the terms of the poverty debate, they find themselves arguing about radical solutions that imagine either a fully employed nation (like a jobs guarantee) or a postwork society (like a universal basic income). Neither plan has the faintest hope of being actually implemented nationwide anytime soon, which means neither is any good to Vanessa and millions like her. When so much attention is spent on far-off, utopian solutions, we neglect the importance of the poverty fixes we already have. Safety-net programs that help families confront food insecurity, housing unaffordability and unemployment spells lift tens of millions of people above the poverty line each year. By itself, SNAP annually pulls over eight million people out of poverty. According to a 2015 study, without federal tax benefits and transfers, the number of Americans living in deep poverty (half below the poverty threshold) would jump from 5 percent to almost 19 percent. Effective social-mobility programs should be championed, expanded and stripped of draconian work requirements.

While Washington continues to require more of vulnerable workers, it has required little from employers in the form of living wages or job security, creating a labor market in which the biggest disincentive to work is not welfare but the lousy jobs that are available. Judging from the current state of the nation’s poverty agenda, it appears that most people creating federal and state policy don’t know many people like Vanessa. “Half of the people in City Hall don’t even live in Trenton,” Vanessa once told me, flustered. “They don’t even know what goes on here.” Meanwhile, this is the richest Congress on record, with one in 13 members belonging to the top 1 percent. From such a high perch, poverty appears a smaller problem, something less gutting, and work appears a bigger solution, something more gratifying. But when we shrink the problem, the solution shrinks with it; when small solutions are applied to a huge problem, they don’t work; and when weak antipoverty initiatives don’t work, many throw up their hands and argue that we should stop tossing money at the problem altogether. Cheap solutions only cheapen the problem.

This month, I had dinner with first-year honors students at a university in Massachusetts. Some leaned right, others left. But all of them were united in their inability to explain poverty in a way that didn’t somehow hold the poor responsible for their predicament. Poor people lacked work ethic, they told me, or maybe a strong backbone or a commitment to a better life. I began to regret that alcohol hadn’t been served when one student brought up the movie “The Pursuit of Happyness,” in which Will Smith’s character performs superhumanly well at his job to leap from homelessness to affluence. The student was no senator’s son: He told us that times were lean after his parents divorced. As I watched this young man identify with Smith’s character, it dawned on me that what his parents, preachers, teachers, coaches and guidance counselors had told him for motivation — “Study hard, stick to it, dream big and you will be successful” — had been internalized as a theory of life.

We need a new language for talking about poverty. “Nobody who works should be poor,” we say. That’s not good enough. Nobody in America should be poor, period. No single mother struggling to raise children on her own; no formerly incarcerated man who has served his time; no young heroin user struggling with addiction and pain; no retired bus driver whose pension was squandered; nobody. And if we respect hard work, then we should reward it, instead of deploying this value to shame the poor and justify our unconscionable and growing inequality. “I’ve worked hard to get where I am,” you might say. Well, sure. But Vanessa has worked hard to get where she is, too.

Matthew Desmond is a contributing writer for the magazine and the author of “Evicted,” which won the 2017 Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction.

Sign up for our newsletter to get the best of The New York Times Magazine delivered to your inbox every week.

Sheila Bair 4 hours ago

Sheila Bair 4 hours ago Image: US Marines

Image: US Marines  Credit: David Foster/Yahoo Finance

Credit: David Foster/Yahoo Finance  Credit: David Foster/Yahoo Finance

Credit: David Foster/Yahoo Finance  Credit: David Foster/Yahoo Finance

Credit: David Foster/Yahoo Finance  Credit: David Foster/Yahoo Finance

Credit: David Foster/Yahoo Finance