Opinion | Op-Ed Contributor

By EZEKIEL J. EMANUELFEB. 25, 2018

Credit Ángel Franco/The New York Times

Hospitals are disappearing. While they may never completely go away, they will continue to shrink in number and importance. That is inevitable and good.

The reputation of hospitals has had its ups and downs. Benjamin Rush, a surgeon general of the Continental Army, called the hospitals of his day the “sinks of human life.” Through the 19th century, most Americans were treated in their homes. Hospitals were a last resort, places only the very poor or those with no family went. And they went mainly to die.

Then several innovations made hospitals more attractive. Anesthesia and sterile techniques made surgery less risky and traumatic, while the discovery of X-rays in 1895 enhanced the diagnostic powers of physicians. And the understanding of germ theory reduced the spread of infectious diseases.

Middle- and upper-class Americans increasingly turned to hospitals for treatment. Americans also strongly supported the expansion of hospitals through philanthropy and legislation.

Today, hospitals house M.R.I.s, surgical robots and other technological wonders, and at $1.1 trillion they account for about a third of all medical spending. That’s nearly the size of the Spanish economy.

And yet this enormous sector of the economy has actually been in decline for some time.Consider this: What year saw the maximum number of hospitalizations in the United States? The answer is 1981.

That might surprise you. That year, there were over 39 million hospitalizations — 171 admissions per 1,000 Americans. Thirty-five years later, the population has increased by 40 percent, but hospitalizations have decreased by more than 10 percent. There is now a lower rate of hospitalizations than in 1946. As a result, the number of hospitals has declined to 5,534 this year from 6,933 in 1981.

This is because, in a throwback to the 19th century, hospitals now seem less therapeutic and more life-threatening. In 2002, researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated that there were 1.7 million cases of hospital-acquired infections that caused nearly 100,000 deaths. Other problems — from falls to medical errors — seem too frequent. It is clear that a hospital admission is not a rejuvenating stay at a spa, but a trial to be endured. And those beeping machines and middle-of-the-night interruptions are not conducive to recovery.

The number of hospitals is also declining because more complex care can safely and effectively be provided elsewhere, and that’s good news.

When I was training to become an oncologist, most chemotherapy was administered in the hospital. Now much better anti-nausea medications and more tolerable oral instead of intravenous treatments have made a hospital admission for chemotherapy unusual. Similarly, hip and knee replacements once required days in the hospital; many can now be done overnight in ambulatory surgical centers. Births outside of hospitals are also increasing, as more women have babies at home or at birthing centers.

Studies have shown that patients with heart failure, pneumonia and some serious infections can be given intravenous antibiotics and other hospital-level treatments at home by visiting nurses. These “hospital at home” programs usually lead to more rapid recoveries, at a lower cost.

As these trends accelerate, many of today’s hospitals will downsize, merge or close. Others will convert to doctors’ offices or outpatient clinics. Those that remain will be devoted to emergency rooms, high-tech services for premature babies, patients requiring brain surgery and organ transplants, and the like. Meanwhile, the nearly one billion annual visits to physicians’ offices, imaging facilities, surgical centers, urgent-care centers and “doc in the box” clinics will grow.

Special interests in the hospital business aren’t going to like this. They will lobby for higher hospital payments from the government and insurers and for other preferential treatment, often arguing that we need to retain the “good” jobs hospitals offer. But this is disingenuous; the shift of medical services out of hospitals will create other good jobs — for home nurses, community health care workers and staff at outpatient centers.

Hospitals will also continue consolidating into huge, multihospital systems. They say that this will generate cost savings that can be passed along to patients, but in fact, the opposite happens. The mergers create local monopolies that raise prices to counter the decreased revenue from fewer occupied beds. Federal antitrust regulators must be more vigorous in opposing such mergers.

Instead of trying to forestall the inevitable, we should welcome the advances that are making hospitals less important. Any change in the health care system that saves money and makes patients healthier deserves to be celebrated.

Ezekiel J. Emanuel is a vice provost at the University of Pennsylvania, the author of “Prescription for the Future” and a partner at Oak HC/FT, a health care investment company.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook and Twitter (@NYTopinion), and sign up for the Opinion Today newsletter.

Above is from: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/25/opinion/hospitals-becoming-obsolete.html

Legal status of Melania Trump's parents raises questions about 'chain migration' (ABC News)

Legal status of Melania Trump's parents raises questions about 'chain migration' (ABC News)

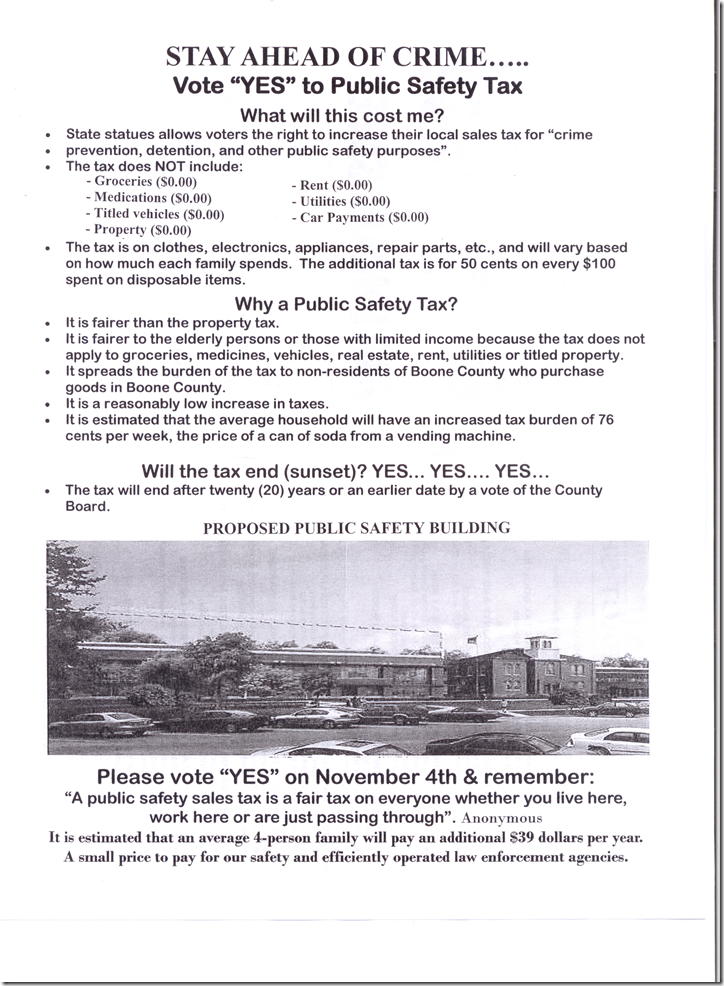

![[PSB%2520tax%25201%2520of%25203%255B4%255D.png]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgGXdATqsigUVE2b6amhJBNUo4ySUK7JzFoFnVYXcjHpbkJxwArvml8G9z_R5o2iLabe6zqVPYqkmHtB1TuBw16eQ_9FO6ZPQ3rKj_Uc7-BOvtgznECJ0mihMOQgzd13u75mFPL3mH13Eiy/s1600/PSB%252520tax%2525201%252520of%2525203%25255B4%25255D.png)