UW model says social distancing is starting to work — but still projects 1,400 coronavirus deaths in the state

March 26, 2020 at 7:25 pm Updated March 27, 2020 at 10:01 am

1 of 2 | Tents sit at Harborview Medical Center’s emergency room on Thursday to keep respiratory patients separate from others in the... (Steve Ringman / The Seattle Times) More

By

Seattle Times staff reporter

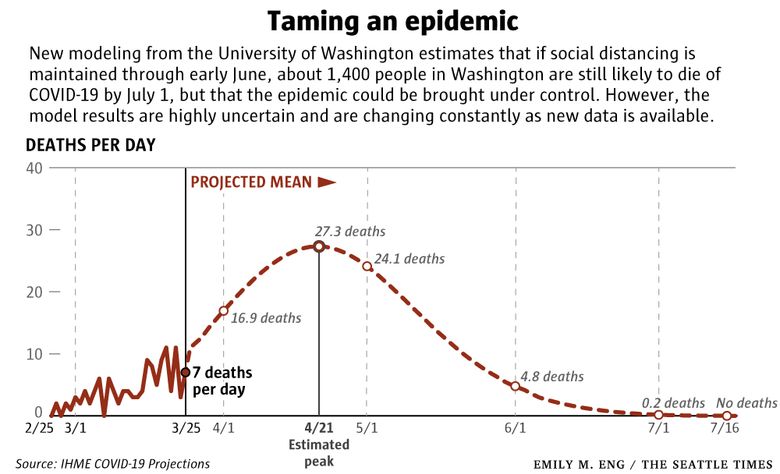

A new analysis from the University of Washington projects that even with strict social distancing from coast to coast, more than 81,000 people in the U.S. — and more than 1,400 in Washington state — could die from COVID-19 by the first of July.

Hospitals and intensive care units across the country are likely to be overwhelmed beginning in the second week of April.

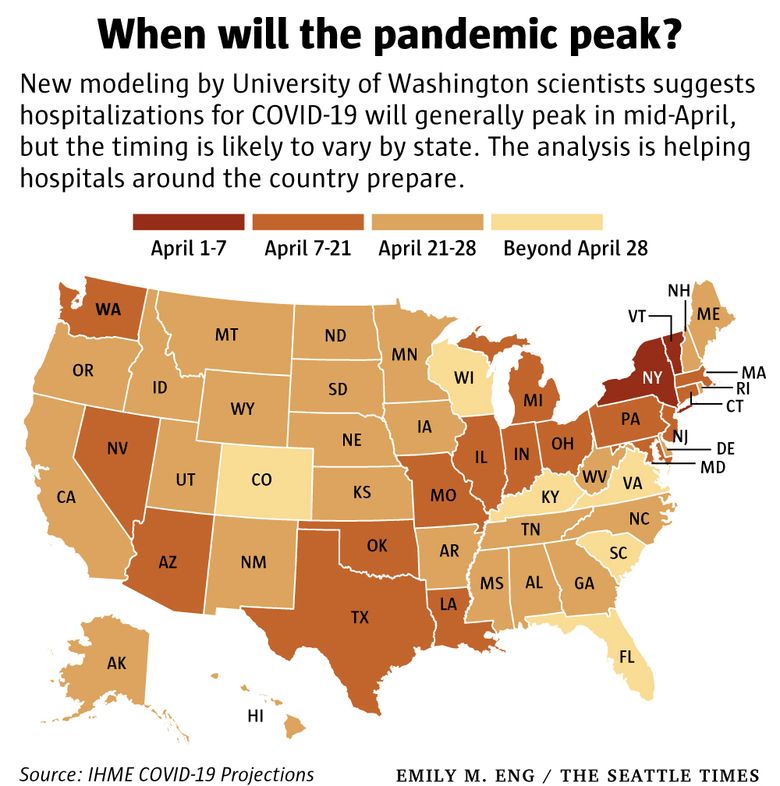

Modeling from the UW’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) forecasts that hospitalizations will generally peak in mid-April, with 64,000 more patients than licensed beds nationwide. The shortfall in ICU beds is estimated at more than 17,000. Demand will be much higher if all states do not adopt and maintain social distancing, says the report, which also examines the anticipated strain on medical systems for every state.

In Washington, there’s no predicted shortage in overall hospital beds, though some individual facilities — including the UW Medical system — will need extra capacity and have already geared up to provide it. The statewide shortage in ICU beds is forecast to reach almost 100 by April 19, the model’s approximate date for when hospitalizations are expected to peak in Washington.

The findings suggest measures to slow the epidemic are making a difference locally. But restrictions will need to continue into late May or early June in Washington and the rest of the country to bring the disease under control, said IHME Director Dr. Christopher Murray.

“The trajectory of the pandemic will change — dramatically for the worse — if people ease up on social distancing or relax other precautions.”

Gov. Jay Inslee acknowledged as much in a briefing on Thursday, saying the stay-at-home order he issued Monday will probably have to be extended beyond the two-week period initially specified as a minimum.

The UW analysis differs from most modeling of the new coronavirus, partly because it relies on the number of deaths across the U.S. and in other countries — which is a more reliable gauge of the epidemic’s course than confirmed infections, which depends on intensity of testing, Murray said. It also takes into account the impact of social distancing measures, something few other modelers have yet quantified.

Still, all of the UW estimates come with a huge measure of uncertainty, the researchers caution. Each model run is based on a thousand projections, which zero in on the most likely result. But the range of possible outcomes remains wide. For example, while 1,430 represents the best projection of total deaths in Washington by July 1, the statistical range extends from 316 to 2,535.

As of March 26, the state had 3,207 confirmed infections and 147 deaths.

“There’s a tremendous amount we don’t know or understand about what explains the variation across communities,” Murray said. “Every day we get more data, we learn more and the forecast will get better and better and more accurate.”

Earlier in the epidemic, the model’s forecasts for Washington were much more ominous, Murray pointed out. But it seems as if the state’s early actions — including companies shifting to remote work, school closures and limits on gatherings — have already had an impact. Hospitals across the state also moved quickly to cancel most elective surgeries and free up beds.

“If you go back even a week ago or 10 days ago, the case predictions from those models suggested we should have had many more cases by now,” Murray said.

Ten days ago, the models were predicting that the UW Medicine System could expect as many as 950 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 at the the epidemic’s peak, said Lisa Brandenburg, president of UW Medicine Hospitals & Clinics. The latest modeling shows a 20 to 30 percent reduction, or an expected maximum of 750 to 650 patients with COVID-19, the respiratory disease caused by the novel coronavirus.

Since UW Medicine and its four hospitals already prepared for the earlier, worst-case scenario — identifying where to squeeze in extra beds and how to mobilize additional staff — Brandenburg said she’s increasingly confident they will be able to handle the surge.

“Generally speaking, it’s very good news for us that the curve seems to be flattening here in Washington state, but it doesn’t mean we don’t still have a substantial amount of work to be done, in terms of taking care of people in the region.”

Hospitals across the state reported 254 admissions of people with COVID-19-like symptoms in the third week of March. That’s double the number two weeks earlier, but only a 10% increase over the week before.

Many medical facilities and hospitals still don’t have enough protective gear, said Cassie Sauer, president and chief executive officer of the Washington State Hospital Association. Another big unknown is whether there will be enough ventilators for critically ill patients, she said.

The UW analysis estimates nearly 20,000 patients nationwide will need ventilators to keep them alive when hospitalizations peak. In Washington, the estimate is 236, and it’s not clear whether the state will have enough of the vital machines, Sauer said.

“I remain massively worried about this whole thing,” she said. “We don’t know enough about the disease. We don’t know enough about how seriously people are taking the ‘stay home and stay healthy’ order.”

However, Sauer also said some hospitals may soon reopen their operating rooms to a limited number of elective surgeries for people with the most urgent medical needs.

The UW projections show that the “first wave” of the epidemic should begin to wane by the end of May or the first week of June. But if social distancing measures are lifted before then, infections and deaths will surge again, Murray warned.

For example, if the number of deaths in Washington peaks around April 20 then begins to decline, as the model currently projects, public pressure to lift the restrictions will become fierce.

“I think the big issue will be in May,” Murray said. “We’ll still have plenty of infections and cases and deaths, but some people will say: ‘We’ve [gone] past the peak. Why can’t we stop social distancing?’

“But if we do stop, and there are still plenty of cases in the community, we can go right back to exponential growth.”

It remains to be seen whether there will be a second wave of infections in the fall, Murray added. Models predicted one during the 2003 SARS epidemic, but it never materialized.

Beginning Monday, Murray and his colleagues will be updating their model daily and posting the results on IHME’s website: healthdata.org.

No comments:

Post a Comment