September 14, 2022

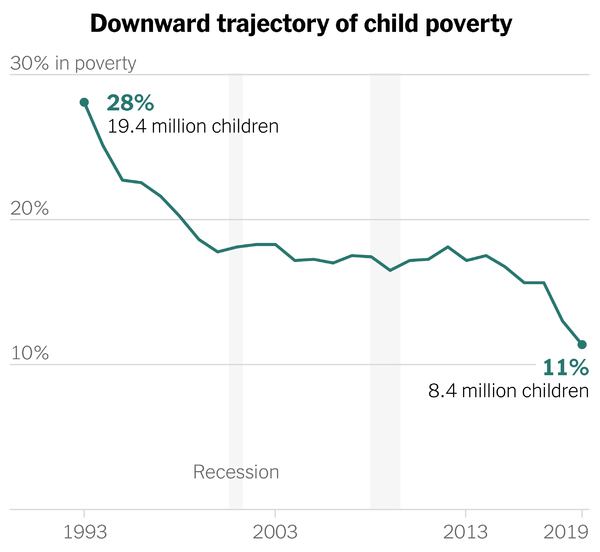

Good morning. Child poverty in the U.S. has fallen by more than half since the early 1990s.

The Tallman family in Marlinton, W.Va.Maddie McGarvey for The New York Times

An unequaled decline

When President Bill Clinton signed a bipartisan bill tightening the rules around welfare eligibility in 1996 — and making many benefits conditional on work — critics on the political left predicted terrible effects.

A few members of the Clinton administration quit in protest. Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan warned of devastating increases in child poverty. The New Republic proclaimed, “Wages will go down, families will fracture and millions of children will be made more miserable than ever.”

A quarter-century later, these predictions look very wrong. As my colleague Jason DeParle wrote this week:

A comprehensive new analysis shows that child poverty has fallen 59 percent since 1993, with need receding on nearly every front. Child poverty has fallen in every state, and it has fallen by about the same degree among children who are white, Black, Hispanic and Asian, living with one parent or two, and in native or immigrant households.

Sources: Child Trends; U.S. Census Bureau; Center on Poverty and Social Policy at Columbia University

How did this happen? The 1996 welfare law turned out to be a case study of different political ideologies combining to produce a result that was better than either side would likely have produced on its own.

Some conservative critiques of the old welfare contained an important insight, Jason told me. Poor single mothers (the main beneficiaries of welfare) were better able to find and hold jobs than many liberals expected. Over the past few decades, increased employment among single mothers has been one reason for the decline in child poverty, according to the study, which was done by Child Trends, a research group.

But the biggest cause was an expansion of government aid. And progressives were the main force behind this expansion. With welfare less generous, Democrats (sometimes in alliance with Republicans) pushed for policies to help low-income workers, such as expansions of the earned-income tax credit and food stamps. Increases in state-level minimum wages also played a role.

Stacy Tallman in West Virginia.Maddie McGarvey for The New York Times

“I don’t know where I’d be right now if I didn’t have that help,” said Stacy Tallman, a mother of three and a waitress in Marlinton, W.Va., referring to Medicaid, tax credits and food stamps.

After welfare reform, the focus of the government’s anti-poverty efforts shifted from people who weren’t working to people who were — and, thanks partly to the generosity of the new programs, child poverty plummeted. The size of the decline, Dana Thomson, a co-author of the study, said, “is unequaled in the history of poverty measurement.”

Dolores Acevedo-Garcia of Brandeis University pointed out that 12 million additional children would be poor today if the poverty rate were still as high as it was in the 1990s. The reasons to cheer this development are both immediate and longer term: Children who spend even modest amounts of time in poverty earn less money and are less healthy as adults on average, research has shown.

Hiding in plain sight

I am guessing that many readers are surprised to hear about the big drop in child poverty since the 1990s. I’ll confess that I was — and I have been covering economics for much of the past two decades. As Jason told me, “It is odd that such a big decline in child poverty has gone almost completely unnoticed.”

In part, the lack of attention stems from a theme I’ve mentioned before in this newsletter: bad-news bias. Journalists and academic experts are often more comfortable reporting negative developments than positive ones. We worry that we come off as blasé or Pollyannaish when we report good news.

The poverty statistics add to the confusion because there are so many different versions. The measure that the Census Bureau calls “official” does not include government aid, which is bizarre, as Dylan Matthews of Vox has noted. And every measure has limitations. The one that Jason used in his story overestimates the impact of the earned-income tax credit and underestimates the impact of the food stamps, for technical reasons. (Neither alters the basic conclusion, as Robert Greenstein, a longtime progressive policy adviser, says.)

Still, I understand why many people are reluctant to focus on the poverty decline. The U.S. has not solved poverty. More than 20 million Americans are poor today, and many others above the poverty line also struggle to afford a decent life. As successful as President Biden has been in passing many parts of his agenda, Congress failed to pass several of his anti-poverty proposals. Those measures would have expanded access to child care and increased the child tax credit, among other things.

Despite these caveats, the decline in poverty deserves to be a major news story. For one thing, it’s legitimately surprising: Even Jason — who has spent more time writing about American poverty than almost any other journalist — acknowledges that welfare reform did less damage than he expected, in part because of the subsequent expansions of aid.

At a time of deep cynicism about government, the drop in poverty is an example of Washington succeeding at something big. “The decline in child poverty is very, very impressive,” Greenstein said, “and it is overwhelmingly due to the increased effectiveness of government programs.”

For more

- The Census Bureau reported yesterday that its more accurate measure of poverty — including government aid — fell to 7.8 percent last year, from 9.2 percent. But that decline was partly the result of anti-poverty programs that Congress has not renewed.

- As part of his reporting, Jason traveled to West Virginia to write about the differences between Cecelia Jackson’s childhood and her children’s lives today. “I’ve got dreams and goals not to need it one day,” she said, referring to the government help she receives, “but for now I’m grateful it’s here.”